Asymmetric power in the information age - I

Chapter 1: Democratic backsliding

This chapter will explain how to conceptualize democratic processes with the tools of complexity science and build an understanding of the complex systems we are all part of. It will be useful to grasp the bigger picture of how a broken info sphere interferes with democracy.

“Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.”

…as the unsourced aphorism famously cited by Winston Churchill goes.

Yet for much, if not all of modern human history, autocracies have been the norm. Even today, only 29% of all humans live in democracies. Up until about 2011, people living in democracies have steadily increased in numbers worldwide. In democratic waves after the Second World War, the end of colonization, and the fall of the Soviet Union, many more democratic nations emerged. In fact, some historians predicted that democratization would be unstoppable.

In an ever-more connected world, the people would see the fruits of democratic societies, take power and liberate themselves of their oppressors. More recently, on the back of the social-media empowered challenges to autocratic rule in Middle Eastern and African nations (Arab spring), many hoped that with the power of a democratic information sphere came the power of a democratic society. These were more hopeful times. But with the exception of Tunisia, a resurgence of authoritarianism, religious fundamentalism, and civil war has since left many Arab nations in a terrible state (Arab winter).

Even faced with these setbacks, the idea of democracy still remains powerful to the politically oppressed, it inspires much strive and a willingness to endure hardships and bloodshed in hopes of a better tomorrow.

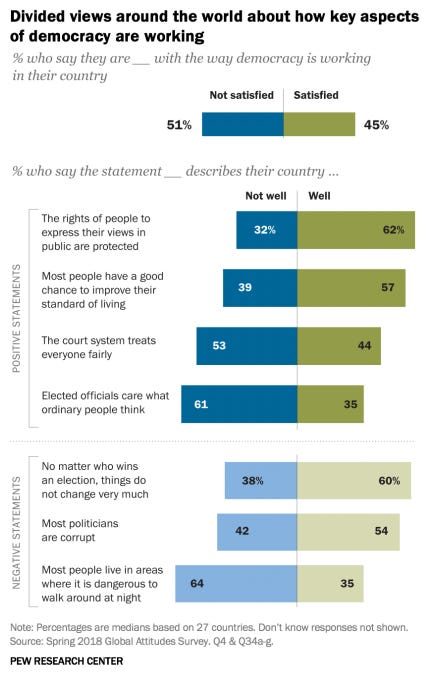

Despite its aspirational ideal, for many people currently living in democratic societies, there is a widespread feeling that the “system” is not working anymore as it used to. Although democracies should work for a majority of citizens and their preferences, recent experiences put this fundamental notion of democracies into question, at least in some democratic nations.

These views are somewhat warranted. Things have been going wrong for some time and democracies are in decline worldwide (Boese VA. et al., Democratization, 2022).

Many smart people have also written about a potential role for social media in that democratic decline. We all love to have our pet peeves and factors to blame. Misinformation. Algorithms. Polarization. Conspiratorial ideation. Globalization. Capitalism. Billionaires. Socialism. Immigration. Foreigners. Politicians. China. Russia. Even the Coddeling of kids might be problematic, according to some popular academics (sorry Prof. Haidt!). The list of blame is endless, and I can acknowledge many grains of truth in some of the alleged culprits.

However, I believe we as a society lack the right conceptual frameworks to talk about democracy, what is going wrong and why we seemingly feel powerless to effect change.

This perceived powerlessness is likely another cause for our bad epistemology and falling into conspiratorial and other magical thinking (Whitson JA. et al., Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2015).

A sizable proportion of people believe in sweeping conspiracy theories involving the “establishment”, “the media” or the “elites”, despite there being no coordination or “great reset” plan between individuals who are part of said groups. Anxiety is palpable and public conversation seems stuck, all while anti-democratic movements are winning democratic elections all around the globe.

What is going on?

Can science provide better frameworks, concepts, and language to think and talk about democracies?

A) Democracy as a non-linear complex system

Complex problems usually require complex approaches

In general, we have a cognitive tendency to award too much credibility to simple explanations; to weigh causal relations disproportionally strong without asking for the relative effect size, and to prefer singular reasons and simplifications that are ‘true enough’ over the fuller messy picture. It is cognitively easy to blame everything on let’s say politicians, foreigners, or globalization, when each factor works just as a small cog in the larger wheel of democracy. I hope that deep down most of us know that these singular explanations can not be the whole story, that there are multiple factors playing a role, despite us having trouble naming all of them, or mentally mapping their influence and contributions, because it is just too complex.

Complex systems in general are counterintuitive to model for our analytical minds, despite most of the things we care about in life being either embedded in them or constituting complex systems by themselves. A cell is a complex system, and so is an organ, our mind, and the human condition. As is an ant colony, social media, the internet, the economy, and the climate.

In these systems there exists no proportionality and no simple causality between the magnitude of responses and the strength of their stimuli: small changes can have striking and unanticipated effects, whereas great stimuli will not always lead to drastic changes in a system’s behavior. — Willy C. et al., European Journal of Trauma, 2003

On top of that, we humans are pretty limited at processing gradual shifts, suck at extrapolating over many dispersed but subtle or indirect phenomena, and are not built to handle non-linearity and feedback loops.

We reduce complexity to heuristics as a way to reach actionable certainty.

Much of science is no different, being done by humans, after all. Many scientific fields thrive by reducing complexity, taking away confounders, and trying to elucidate the minimalist mechanistic essence of causal interactions. Don’t get me wrong, there is nothing wrong with that, this has been a successful and valuable approach to building up much of our current body of knowledge of how the world works. Yet how is a reductionist approach supposed to work in systems that only become functional when a certain complexity is reached?

Studying the complexities and impact of social media is difficult. For example, what can really be said about the effect and impact of Instagram on the mental health of teenage girls? Mental health is a fuzzy subjective concept. Scientists can track indicators and proxies, like suicide numbers, but they have many biological, psychological, and societal antecedents. However, if let’s say suicide numbers double in female Instagram users compared to non-Instagram user cohorts, there are causal questions to be asked. Are female suicides really up because of Instagram? Can Instagram cause something so dramatic? Are suicide-prone teenagers maybe more likely to engage with Instagram? Scientists would like to study these questions, yet big platform companies are doing everything they can to not give academics access to data (but that is another topic). So scientists have to keep scratching at the edges, is it really a surprise many studies find inconclusive evidence of social media harm (Kross E. et. al., Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2021) ?

How is a reductionist approach supposed to work in systems that only become functional when a certain complexity is reached?

Complexity is a well-known problem in mathematics (Meyers RA, 2012) social sciences (Elliott E. and Kiel DL, University of Michigan Press, 1996), biology (Mazzocchi F., EMBO reports, 2008), medicine (Willy C. et al., Eur J Trauma 2003), and economics (Gasparatos A., Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 2008).

In psychology, some researchers go so far as to even avoid causal inference explicitly because of complexity (Grosz MP. et al., Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2020). In my opinion, this is wrong-headed. Accurate causal inferences are important for science and non-linear systems are still based on causal interactions, albeit complex ones. We can predict weather likelihoods, despite getting it wrong sometimes because of chaotic dynamics. There is no great workaround, complex systems require scientists to study them as a whole, with all the caveats, limitations, and uncertainties attached to them.

I hope now it becomes a bit more understandable why it has been difficult to scientifically pin down the impact of our fragmented info spheres and broken epistemology on wider society. A pre-registered systematic review of almost 500 studies finds a lot of evidence that digital media can increase political participation, but often is detrimental and can erode democracies (Lorenz-Spreen P. et al., Nature Human Behavior, 2022).

Our results provide grounds for concern. Alongside the positive effects of digital media for democracy, there is clear evidence of serious threats to democracy. Considering the importance of these corrosive and potentially difficult-to-reverse effects for democracy, a better understanding of the diverging effects of digital media in different political contexts (for example, authoritarian vs democratic) is urgently needed. To this end, methodological innovation is required. This includes, for instance, more research using causal inference methodologies, as well as research that examines digital media use across multiple and interdependent measures of political behaviour.- Lorenz-Spreen P. et al., Nature Human Behavior, 2022

I think it is fair to say that science has not solved social media yet, especially when it is unclear what scientific disciplines need to engage.

Sociologists? Psychologists? Mathematicians? Algorithm engineers? Data analysts? Neurobiologists? Graph, network, or game theorists? Disinformation researchers? Probably we need all of them, working together, and then some. On top of that, many current studies still use a reductionist framework for investigations, looking at indicators, single metrics, or phenomena, rather than approaching certain questions from a complex system’s perspective (I hope my article here might make the case, feel free to reach out). Two of my biggest worries when it comes to current scientific uncertainties can be summarized in two questions:

Are we looking at the right things to scientifically assess whether social media dynamics cause harm to democracy?

How can we hope to get a scientific answer before it is too late and irrevocable harm has been done?

I don’t know, but I believe it is important enough to try for an answer today.

To do that, we first have to get a workable overview of how to conceptualize democracies and social media as interacting complex systems.

This is not a small task. The most useful frameworks I have found within the scientific literature to think and talk about the societal problems I see come from areas of research as disparate as physics, neuroscience, socioeconomics, and systems biology all the way to control theory, mathematical modeling, epidemiology, statistics, and game theory.

Basically, all social and natural sciences which work toward understanding complexity and investigate the behavior of complex systems. Without going into too much detail (here is an excellent scientific paper for that), the idea is to use scientific concepts, tools, and methods developed by these domains to try to apply them to us.

Complexity science tries to chart the macroscopic behavior (in this case of messy little autonomous humans) and describe systemic trends of the bigger systems we are part of, i.e. fragmented online information spheres, and of course democracy itself.

Fair warning:

Attention is a critical good and I don’t want you to get frustrated.

The next sections of this chapter are going to put a lot of cognitive strain on the reader, so I actually recommend jumping ahead to Chapter 2 for most readers. This is where we explain the asymmetric forces on social media, why influencers dominate conversations, and how information combatants exploit vulnerabilities.

For the deep or academically inclined readers, the next sections could be useful to rethink the systems we inhabit. Take your time, or revisit these sections after first jumping ahead to the more important Chapter 2.

B) Tools from complexity science

The vocabulary and principles to conceptualize complex systems

System descriptions

When talking about systems, complexity science uses terms like ‘robustness’ (sensitivity to micro-scale perturbation), ‘stability’ (resistance to change over time), ‘adaptability’ (how viable a system remains during transformational change), ‘equilibrium states’ (local optima that reinforce robustness) and so on. For us, it is sufficient to know that researchers look at a set of indicators, economic, historic, physical, political, or social (e.g GDP, unemployment rate, press freedom score, corruption index, suicide rates, graduate degrees) and then try to figure out how these indicators impact the stability or robustness of democracies.

At the risk of oversimplification: complex system researchers try to understand what are the fundamental parameters impacting the systemic behavior of democracies to then be able to build hypotheses on how to strengthen democratic systems or make predictions about what societal forces or trends might indicate or bring their demise.

An example of such hypothesis would be that economic inequality leads to institutional capture by elites, thus reducing the institutional adaptability (and with it threatening long-term stability) of democracies:

Democracy presupposes a basic equality of influence. As economic inequality increases, so too do differences of influence over institutions. Those who have substantial financial resources are better able than those without to influence institutional change. — Wiesner K., European Journal of Physics, 2019

The theory is assisted by observational data that for example considers that policy outcomes in the US (and elsewhere) reflect not the majority view but are better predicted by the preferences of the wealthy.

Indicator-based system descriptions are of course to be taken with care, just because some indicators might be associated with certain outcomes does not mean that they are causally related, nor is their directionality of influence always easy to discern. (Complex systems, remember?!?)

Policy outcomes in the US (and elsewhere) reflect not the majority view but are better predicted by the preferences of the wealthy

Does institutional capture cause economic inequality or is it the other way round? Are there other confounding factors, for example, elite overproduction or age/race/sex demographics, that better explain institutional capture? Or can events like a recession better explain economic inequalities? It is a mess because, in complex systems, all the different indicators are somehow involved in shaping the total and furthermore react together in often chaotic, synergistic, and unpredictable ways. This brings us to the next point:

System dynamics

Τα πάντα ρει - everything flows [attributed to ancient Greek philosophers]Outside of identifying critical indicators, another way how the complex system’s view can aid our understanding of democracies is when it comes to dynamics; namely feedback loops, tradeoffs, and non-linearity.

In biological systems, for example, a cell’s metabolic, transcriptional, or signaling networks, we differentiate between positive (as in amplifying) and negative (as in reducing) feedback loops. These are mechanisms that react to a certain perturbation to the status quo (sudden availability of sugar, or drop in oxygen availability) by either causing other cellular processes to run faster, shut down, or perform a different function. Feedback loops perform many important functions, from regulating stability of dynamical systems to optimizing signal-to-noise ratios for cellular decision-making (Hornung G. et al., PLOS Computational Biology, 2008).

In democratic systems, feedback mechanisms are ubiquitous as well. Gerrymandering in the US is a prominent example of a “positive” (as in amplifying) feedback loop (Wang SSH. et al., PNAS, 2021) where the electoral winner gets to draw voting district lines that will favor him in subsequent elections. “Negative” (as in reducing) feedback loops include the separation of powers into co-equal legislative, judiciary, and executive branches. When one branch exceeds its function in an attempted power grab, the other two reign it in and thereby reduce its power, which is overall good for the stability of democracies as a system. There are many more such feedback loops… freedom of the press is negative feedback on political corruption, grassroots movements are a positive feedback for policy change, voters punishing bad behavior or performance from politicians is another negative feedback loop, etc… you get the point. Lots of causal interactions make sure the complex system of democracy remains robust to many types of perturbations (e.g the inevitable individual failings of us error-prone humans that are part of the system).

Voters punishing bad behavior or performance from politicians can be seen as a negative feedback loop

Tradeoffs are a common theme in complex systems too, either because there are always limited resources to be allocated (and allocating them to one aspect means there is less left for others) or the functional optimization of one feature comes at the cost of vulnerability in another.

Trade-offs are well studied in economics, biology, physics, and math. Examples include how just-in-time manufacturing optimizes for cost-reduction and speed but makes the supply chain less robust towards disruptions (Jiang B, IMF economic Review, 2021), for example by unexpected viruses running havoc causing labor shortages or lock-downs…

Many tradeoff examples come from biology, e.g needing to boost survival mechanisms in resource-poor environments cause bacteria to lose adaptive capacity in the form of speed and accuracy (Lan G. et al., Nature Physics, 2012)

Both feedback and trade-offs often go hand in hand and play a role in control theory in biology (Cowan NJ. et al., Integrative & Comparative Biology, 2014) and many other areas of science and engineering (Veccio DD. et al., J. R. Soc. Interface., 2016)

Control theory has arisen from the conceptualization and generalization of design strategies aimed at improving the stability, robustness, and performance of physical systems in a number of applications, including mechanical devices, electrical/power networks, space and air systems, and chemical processes — Veccio DD. et al., J. R. Soc. Interface., 2016

non-linearity

Non-linearity in math and science is a term to describe system interactions where the change of the output is not proportional to the change in input and may appear chaotic, unpredictable, or counterintuitive. Evolving complex systems are almost always non-linear because their reaction to perturbation usually depends on the specific state there are in at a specific moment in time, and the space of potential states might be infinitely large. This might sound complicated but think of it as acknowledging that we do not live in a vacuum, but in a constantly changing environment that interacts with us, we come with a unique history and we are not a perfect machine. For example, if you give me the input that ‘I suck’ today, I might laugh at you, or get angry and push you away, or do something completely different, depending on my initial state of mind, my experiences, but also our shared history together. Same input, disproportional output. (disproportional output does not mean random, it might however be non-deterministic, probabilistic or unpredictable)

Non-linear systems have disproportional output

Disclaimer: Please consider that the dynamics of non-linear evolving systems is an area of active study in many disciplines, far exceeding my own capabilities to even just outline properly (here might be an interesting book for the mathematically inclined). In fact, because it is so vast an area of research, I am very uncomfortable to even create the false appearance that I have any good grip on the various research topics. I do not. At most, I have limited system’s biology experience which gives me some conceptual and working familiarity with complex living systems.

In any case, what I feel comfortable doing is trying to sketch out common themes in systems science in order to have a conceptual framework to talk about democracy as a dynamic, non-linear complex system, because I find it useful and increasingly necessary to understand our world.

Finally, there is one last point we have to cover. Dynamic complex systems perform complex functions.

C) Complex functions in democracy

Understanding emergence and meta-phenomena

Living is an emergent meta-phenomena. It is the result of implementing a set of complex functions. Staying alive requires navigating the environment, supplying oxygen and nutrients to cells, repairing tissue damage, and propagating the pattern of existence forward without dropping the ball even once. Living is not just one thing, it is like a juggling act if one could juggle a torch, an ax, and a baby while running a marathon. In short, it is weird and messy and complicated. There are many different shapes of “living”, not least because of the problem with the definition of what constitutes living and what does not (which is also not agreed upon and up for discussion, but I digress).

If we understand humans as the dynamic, non-linear complex system consisting of 34 trillion cells that we are, “living” requires a specialized set of micro & macroscopic actions that differs from what a tree or a bacterial colony has to do to stay alive. This trivial observation is still somewhat surprising since many living things are essentially implemented by and the product of trillions of cells that are mostly made up of similar building blocks (nucleic & amino acids, proteins, lipids, sugars etc…) and these cells observe similar basic principles of physics, chemistry, and cell biology.

The point is: Largely similar autonomous units (cells) behaving a bit differently can produce vastly different complex functions, collective behaviors, and with it new emergent phenomena.

Although a bumpy analogy, macrosystems like nation states can be understood as somewhat “living” organisms too, and are certainly shaped by a set of micro & macroscopic actions as well (nation states are implemented by and product of the collective actions of their constituent parts, meaning us largely similar autonomous humans).

We humans collectively perform the complex functions that keep any system of governance ‘alive’.

It does not matter if that nation-state is a democracy or a dictatorship, or something in between, as long as the same system propagates forward in time, it can be considered “alive”.

However, an argument can be made that there are only a few robust ways to uphold these complex functions that keep the respective ‘system of governance’ alive, and failure to do so will lead to instability, dysfunction, and decay; ultimately ‘death’ of the old system (often finalized with a coup d’état) and the leftover constituent parts either transition towards a new systemic state (new regime) or collapse and chaos (failed stated).

Let’s take a look at (some of) the complex functions any stable system of governance needs to perform:

resource allocation between citizens and/or subjects

Every macrosystem, be it a kidney, an ant colony or a governing body has to navigate the tradeoffs of resource distribution. Stable systems distribute resources in a way that adds to their robustness or maintains equilibrium, whereas failure to distribute appropriately can lead to system collapse. Economists have long mapped the often counterintuitive relationship between economic disenfranchisement of the masses, or the threat of new taxation of a rich elite, with political transitions (Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. The American Economic Review, 2001, De Mosquita B. et al, MIT Press book, 2003, Besley and Kudamasu, 2008).

Stable autocratic systems make sure that resources flow primarily to secure the loyalty of the power-holding elite in the autocracy, meaning the military, police, select government officials, key bureaucratic functionaries and party power brokers (Gallagher M. & Hanson J, 2009). Resources for public goods (like infrastructure, hospitals) or the wider population (education, social programs) are limited or not considered at all.

Stable Democratic systems have to allocate and redistribute resources among power holders to maintain robustness and stability too, but in the democratic case, power lies with masses of voters and the interest groups, unions, parties, intelligentsia, religious leaders, and economic elites who influence them.

From a system’s perspective, the complex function of ‘resource allocation’ has at least two implementations that historically seem capable to sustain stable governments (keeping them in equilibrium), while variations from these implementations might cause inherent instability to the respective system.

For example, distributing resources to the masses might be a bad strategy for autocratic rulers, as they might face a coup d’état from an insurgent who promises the actual power holders in autocracies (military generals, bureaucrats, etc) a bigger share of the resources currently ‘wasted’ on the powerless masses. It has been well observed that after a successful military coup d’état, resource distribution towards the military increases. Some studies even suggest it is often the reason why a coup d’état happened in the first place (Leon G., Public Choice, 2014). Let that sink in for a second. From an autocratic system’s perspective, spending on the “people” is considered resource mismanagement that can make the system less stable.

(To be honest, I recommend this excellent and entertaining video based on “the dictator’s handbook”, to get a decent intuition surrounding resource distribution and power… also, it’s fun!)

On the other hand, failures to redistribute and allowing resources to accumulate in only few elites might be a bad strategy for democracies. Democracy presupposes a basic equality of influence, so any type of societal inequality might subvert democracy in varied ways (we mentioned institutional capture by elites), albeit a scientific consensus has not been reached on this issue (Savoia A et al., World Development, 2010 , Acemoglu D. et al., MIT economics, 2015 , Page & Gilens, University of Chicago Press, 2020 , Dacombe R. et al., Representation, 2021).

On top of that, distributing resources too unevenly towards particular interest groups to ensure (“buy”) voter loyalty of that group challenges political legitimacy of the distributing body with not-favored voters, and with it the stability of democratic systems.

This brings us to the next point: political legitimacy

maintaining legitimacy to direct coordinated action

Political legitimacy is an ongoing scientific research area with both normative and quantitative approaches being advanced to measure and analyze constituent factors of political legitimacy. There are many different lines of thought, from the Lockean notion of ‘consent of the governed’ to Weber’s empirically observable “belief in legitimacy”, to questions if definitions of ‘political legitimacy’ even make sense in autocratic rule (Gerschewski, J., Perspectives on Politics, 2018).

However, what can be said is that legitimacy in democratic systems is a multi-factorial issue that can not simply be measured by asking people if they are satisfied with democracy (Linde & Ekman, European Journal of Political Research, 2003).

Individuals within any larger democratic system will have different political positions, preferences and problems that it wants the governing structure to accommodate to recognize its legitimacy, and prolonged failure to do so might lead to disengagement from the system and withdrawal of cooperation. However, democracies are usually robust to a subset of citizens not recognizing the political legitimacy of the current power holders.

[…] generalised or diffuse support (e.g., support for regime principles) does not emerge overnight. Rather, it must be built on a record of acknowledged

regime performance […] that are not only of an economic nature, say, a matter of economic growth or social reforms.Crucial for the creation of a reserve of generalised system support is also the regime’s capacity to maintain order, to maintain the rule of law, and to otherwise respect human rights and the democratic rules of the game. — Linde & Ekman, European Journal of Political Research, 2003

In autocracies, political legitimacy is more nebulous, because it is unclear who it addresses in an unequal society. Is political legitimacy irrelevant when behavior is enforced through violence or coercion? Are claims to legitimacy solely dependent on the loyalists, military leaders, and bureaucratic functionaries of autocracies, but not wider society?

Legitimacy is a relational concept between the ruler and the ruled in which the ruled sees the entitlement claims of the ruler as being justified, and follows them based on a perceived obligation to obey. The legitimating norms must constitute settled expectations in order to be fully effective and must be actively transferred. — Gerschewski, J. Perspectives on Politics, 2018

So while political legitimacy was, is, and will likely remain a hotly debated topic, most agree that maintaining legitimacy is necessary for any government or institution to ensure the cooperation of the majority of its constituent parts.

Another way of looking at the governing people/institutions of a nation-state then is that they are central control hubs that maintain the stability and robustness of a system through the collection of system-relevant information, integrated decision-making, and enforcement of coordinated actions (cooperation).

Creating legitimacy in democracies is important because it allocates decision power over the rules of cooperation to the democratically elected control hub (i.e government) via for example making laws or by creating financial incentives (i.e power of resource distribution). We see already that complex functions also interact with each other, because a nation-state is a complex macro system.

Regulation and control of cooperation

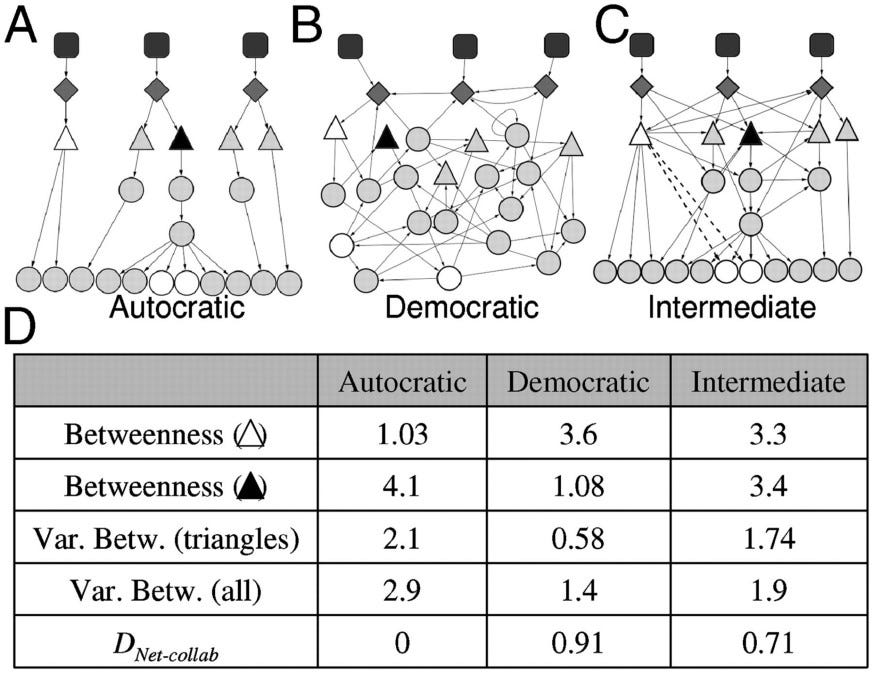

All control hubs, biological, corporate, social or societal, depend on and use the power of hierarchical structures to enforce coordination and control the behavior of individuals.

Hierarchical structures either instigate, guide, monitor, enforce, or punish behavior as well as disseminate decisions and information between regulatory layers.

That does not mean there are no differences in the shape of hierarchical structures between different systems, nor are hierarchical structures the only way to get emergent behaviors (see for example control hub-free swarm intelligence).

In many complex systems, regulation and control is a fascinating field of study, and researchers have identified many shapes of how influence can or might be asserted by one constituent part onto others of the same system by abstracting them in networks (Bocaletti S. et. al., Physics Report, 2006).

Autocratic hierarchies, for example within the military, usually follow a linear chain of command and top-down dominance between the layers. Democratic hierarchies show higher connectivity within and between layers, asserting control via multiple intermediaries. Some research suggests that the more complex a system gets (i.e the more constituent parts to regulate), the more likely it is supported by regulators that collaborate with other regulators to exert control, rather than strict dominance chains (Bhardwaj et al., PNAS, 2010). This could also be a feature of how the control system arises in the first place:

Democratic hierarchies are built bottom-up through election while autocratic hierarchies are built top-down through domination. Both, however, have power asymmetries between the weaker citizens and the stronger politicians, which are amplified the stronger the hierarchies are. — Toelstede, B. , Rationality and Society, 2020

Control hubs collecting and processing system-critical information and instigating collective action is a critical feature for a system’s adaptability, for example, to react to environmental threats or changes. We can illustrate this with another complex function:

system adaptability for self-preservation

Our world is non-linear, the environment is constantly changing, and complex systems need to adapt to new circumstances to remain viable through environmental challenges, or transformational change.

Complex systems sometimes have the means to actively defend themselves from destructive outside influence, be it an immune system that learns to thwart parasites, an ant colony reorganizing itself during disease, social media algorithms getting smarter at filtering bots, to a military increasing its capabilities to defend the sovereignty of the state. Failure to self-defend can lead to critical system collapse.

Most (all?) living systems we know of are adaptive, from bacterial colonies to plants to humans to societies, these systems might even need to have evolved self-defense to remain viable in environments where (for example) they have to compete with other living adaptive systems for resources... maybe let’s phrase it more accurately:

It would be unrealistic for certain complex systems to have survived in competitive environments if they had not adapted to it by evolving their self-defense capabilities.

Self-defense is so important that software and cybersecurity researchers try to create artificial immune systems to detect and protect against threats to distributed power systems (Alonso FR et al., IEEE, 2015) or even complex IoT ecosystems (Aldhaheri S, MDPI, 2020).

Both democratic and autocratic societies rely on self-defense to be viable.

For democracies, some research suggests that increases in network alliances dramatically reduced the threat of war and regime change (Jackson MO., PNAS, 2015), and that good self-defense capabilities through alliances might even foster democratization (Gibler & Wolford, 2006). A nation with a weak army and no alliances (= incapable of systemic self-defense) will likely not remain viable as a system when needing to adapt (transformationally change) to ever new circumstances of a shifting world (Powell et al., Democratication, 2018).

A nation with strong alliances has better chances to emerge whole through rapid transformational change, as the Ukrainian people are currently showing us in their rapid systemic transition to democracy. Indications look promising, albeit that history has not yet been written.

Alright, that wraps up our primer on complex system science for democracy. The last thing we need is to apply these concepts to a real-world example. How about something “easy and uncontroversial”, like I don’t know, Afghanistan?

D) Understanding democratic failure from a complex systems perspective

Applying complexity science to the real-world

Many people, including decision-makers, were surprised at the sheer speed of the collapse of the democratic Afghan government once the US troops withdrew and the Taliban came marching in. Because complex system behavior is often highly dependent on initial conditions, to understand what happened, we have to start by looking at the recent history first.

Political legitimacy of various power holders in Afghanistan was and has been enforced by military power for a long time, most notably since the Soviet-Afghan War, which was weaponizing its populace over decades and shifting traditional power structures and hierarchies away from clergy, community elders, intelligentsia, and military in favor of powerful warlords ruling through dominance hierarchies (Kakar, M. Hassan, University of California Press, 1995). The withdrawal and breakdown of the Soviet Union led to an ongoing civil war between rivaling Mujahedeen parties and ultimately a failed state with shifting militias like the Taliban (propped up by Pakistan) taking control of many regions. From a system’s perspective, Afghanistan’s systemic state was not in any equilibrium, nor a single system for that matter, but multiple competing smaller systems based on military hierarchical structure and autocratic rule fighting for territorial supremacy in the region.

When the US started occupying the country, despite easily taking control of the capital and its institutions, there was no effective ‘centralized control hub’ in place they could have taken advantage of and tried to transition towards performing the complex functions of government in a more democratic way. There simply was no state-wide system, it needed to be built. They did take Kabul and made whatever local system existed in Kabul and its surroundings more democratic, but most of the US’ resources and energy would still go towards fighting other competing systems (insurgencies, the Taliban, Pakistan), almost identical to what the warlords did before. Fewer resources went toward trying to expand their local democratic system by integrating more of the constituent parts, the Afghan people., and build a state-wide system (i.e true nation-building).

The Afghan state collapsed because it lacked legitimacy in the eyes of the people. The sources of this legitimacy crisis were multiple and interwoven. First, the 2004 Constitution created a system of governance that provided Afghan citizens with few opportunities to participate in or have any meaningful oversight of their government.

Second, the international coalition was focused on fighting an insurgency and consolidating power — missions distinct from and often at odds with democracy-building.

Third, the intemperate rule of President Ashraf Ghani (2014–21) hastened state collapse. Ghani, who kept a tight, close circle and had only a narrow base of support, micromanaged both the economy and the state, and he discriminated against ethnic minorities. […] his behavior was more authoritarian than democratic.

Finally, it was only with the support of Pakistan that the Taliban could reemerge as a political and military force. — Murtazashvili JB., Journal of Democracy, 2022.

Despite being made pro-forma a ‘democracy’ during US occupation, the macro-system “Afghanistan” was not successfully changed where it counts: At the underlying constituent parts performing complex functions like distributing power among the supposed power holders, i.e the governed, and with it create political legitimacy in the whole country. Despite citizens being given the right to vote, the legitimacy to govern the whole country “democratically” was instead created and enforced through autocratic means, like bribes to loyalists. So once the current power holders fled, it was all too easy to get rid of the democracy and impose a new order.

Creating legitimacy through autocratic means is of course only one example of how the constituent parts of the Afghan system were performing complex functions at odds with democracy. Similar arguments can be advanced about the complex function of resource allocation, where the US-installed Afghan government showed itself being famously corrupt, hoarding all the resources within a small group of elites and loyalists (like in autocracies) and not distributing them to the people. Another breaking point was the way how coordinated action was instigated, through military power and bribes, rather than popular participation and representatives. Lastly, the Afghan government as a system also failed to build sufficient self-defense capabilities to protect itself, with the lack of any alliances and with the Afghan army famously falling apart or joining the enemy.

Again, while we see that the Afghan situation is undoubtedly complex, it becomes navigatable and comprehensibly so with the right conceptual framework.

Afghanistan’s democracy did not suddenly fall with the withdrawal of the US, it was a failed state governed by autocratic mechanisms before the US came and its autocratic dynamics remained robust despite the ‘perturbation’ of US occupation.

Then again, I will be careful to not assign blame. Changing complex system dynamics, especially when it comes to nation-building, are difficult topics where much smarter people than me will bite their teeth out. I also withhold judgment on the morality of the supposed endeavor, because I certainly have too superficial knowledge about the topic.

I just wonder: How surprised should we really have been about the fact that Afghanistan’s democracy rapidly disintegrated and transitioned towards autocratic rule under the Taliban once the US (and international institutions) withdrew last year? Everything we knew (or could have known) suggested so. Our surprise seems to me more like a reflection of our own ignorance than a response to an unpredictable unfolding of history or a black swan event. (Also, we should not have any illusions that Afghanistan will have any stability under the Taliban, their taking control is likely just as transient and will break down into civil or geographical disintegration when transformation change is required, or the next powerful perturbation arrives)

Alright, for our purposes, I think you get the point. Seeing the world is made up of non-linear dynamic complex systems can be useful, even illuminating, it allows us to conceptualize common themes and find a vocabulary to describe wildly-different and emergent macro-phenomena in a useful way: To intuitively understand them better without false simplifications.

Conclusion Chapter 1:

Understanding democracies as non-linear complex systems gives researchers and citizens the tools to ask more useful questions and gain insights about the mechanistic needs driving the system we are part of. Most importantly, it sharpens the framework of possible actions individuals, groups and institutions can take to effect change.

A society wishing to live in a democratic system has to perform complex functions arising from our collective behavior, and transitioning towards those functions is difficult and often unsuccessful (Arab Winter comes to mind, or post-Soviet Russia). For the lucky people and societies already living in democracies, upholding them is more a question of maintaining existing control systems in place, implementing adaptive responses to systemic threats, and managing new environmental challenges. Democracies have faced and mastered challenges before, in fact, in the later half of the 20ths century, they seemed better equipped to do so than any other form of governance.

Yet the democratic backsliding observed by researchers, journalists, and citizens in recent years marks a worrying transition from the self-stabilizing equilibrium of democracy toward a new system of democratic instability and dysfunction. That transition is a reflection of something going wrong, and is showcased by the failings or corruption of critical complex functions and dynamics, be it the dismantling or abuse of critical feedback loops (e.g independent journalism, voter manipulation) or the implementation of complex functions at odds with democratic processes (e.g voter disenfranchisement, unequal resource allocation, weak/no separation of powers). While this is very much a gradual process, the longer it takes us to come back to a democratic equilibrium state, the harder it will be.

We need to identify what pushes our democratic system in the wrong direction, and we need to do so fast.

Read next: Chapter 2: How asymmetry favors the powerful