Disparage, disorient, dispute

The manipulation playbook of anti-science actors, part 3

Background

Confusion is a natural part of life arising from error-prone communication, conflicting information, or unexpected observations. When confused, we often misinterpret information or situations in a way that conforms to our prior expectations, knowledge, and biases. The latter is what makes confusion interesting for anti-science actors as a tool of information warfare.

Media manipulators — a mix of influencers, media owners, politicians, activists, grifters, entertainers, marketing departments, shadowy businesses, and clandestine actors — sow confusion in order to create space for unsubstantiated worldviews we might already be inclined to hold. Beliefs that are ultimately either unjustified given the current evidence, or directly contradicted by scientific knowledge.

They might give us strawmen we can utilize in our own motivated reasoning, or lull us in comfort that our in-group or the silent majority believes the same thing as we do. They might use information asymmetries to obfuscate the state of evidence, or take our minds on a slippery slope to scare us into rejecting action or change. They want to dull our senses to ignore contradictions, plead for exceptions and rewrite histories with causes that never were, all to justify the status quo.

Confusion is powerful because it breeds paralysis for our agency and sabotages collective action for the public good. Additionally, confusion instills us with anxiety, frustration, and anger; these are activating emotions that can be targeted and channeled toward radicalization.

In the battlespace of information, we are civilians in harm’s way.

The most cynical or dishonest media manipulators might sow confusion for express political ends. Unfortunately, there is no rescue in sight for most civilians globally. For people outside of the European Union’s protection, there is little hope that governments will intervene and implement regulations to safeguard their human rights online.

But even within the EU today, if we are not careful with whom we trust, our attention, money, and ultimately agency are up for grabs for the next influential charlatan who comes ambling along.

Understanding what tactics they are most likely to use is the least we can do to start working on a defense strategy.

Well, at this point, you know the drill. Downloadable high-resolution versions are at the end of the article. Previous manipulation tactics can be found here: The playbook of anti-science actors — part 1 , The playbook of anti-science actors — part 2

Let’s get started.

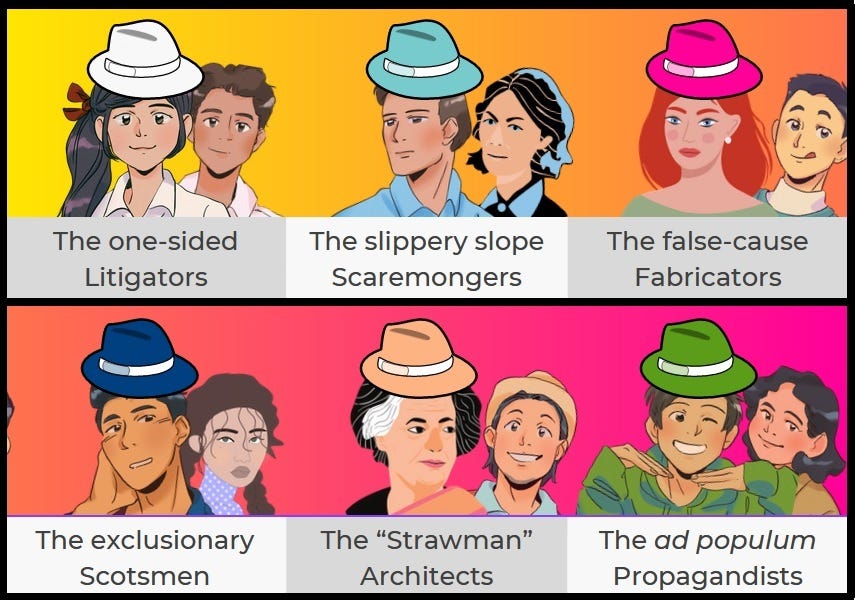

The new archetypes:

The one-sided Litigators

How they work:

Information asymmetries — when one party knows more than the other — pose a risk for opportunism in business, management, and human relationships (Bergh D., 2018), especially when individuals with low ability or knowledge overestimate their own competence in a topic (Dunning & Kruger, 1999).

Media manipulators can hijack information asymmetries in science by providing only one-sided facts and narratives in support of false claims or hypotheses. As seasoned litigators, manipulators take advantage of our ignorance of details to craft seemingly compelling cases for alternative theories or poke holes into established theories. This works because we tend to rely on a cognitive bias known as the availability heuristic to evaluate merit of a claim (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). If we have no expert knowledge available, we are more inclined to believe the narratives on offer.

A related asymmetric information strategy is to pronounce the (supposed) absence of any counter-evidence as evidence for a claim, which might mislead individuals to accept prima facie implausible claims or not reject them to preserve cognitive consistency (Vu L., et al., 2023)

“What can be asserted without evidence can also be discarded without evidence” — Hitchens’ razor (named after Christopher Hitchens)

Case study: Taking uninformed watchers on a hero’s journey

John Stossel is a former award-winning television presenter for ABC and later Fox News who has been in the media game for more than four decades. As a libertarian ideologue, author, political activist, and pundit, his content focuses on conservative classics such as free market absolutism, big government criticism, and opinionated essays of why an inconvenient scientific consensus on things like smoking or climate change is actually wrong. The latter I am sure has nothing to do with his countless affiliations to climate denial networks, funders, think tanks, and Koch-money-sponsored NGOs pretending to be academic institutes.

The seasoned media personality has been criticized over the years for his lack of balance of coverage and distortion of facts on his part by organizations such as FAIR and media matters. His shtick would include the superficial veneer and mannerisms of an investigative journalist. Interviewing supposed expert sources, quoting media reporting of established outlets, asking seemingly tough questions, and sprinkling in enough truthful bits to be hard to discard while ignoring inconvenient facts or context. The overarching conclusions would however always fall in a very one-sided direction.

Since 2019, he realized that there is a much larger market for his learned journalistic make-belief skills by creating Stossel TV, a media-of-one outlet that posts videos on YouTube, his own website, and social media like Facebook and Twitter. Let’s just say the quality of his one-sided reporting has not increased since. But he got even more successful.

“Stossel carefully crafts narratives that directly oppose nearly everything we know to be true […] you might think twice about blindly believing the figureheads on your screen”

… a recent article about Stossel’s modus operandi would claim. But how exactly does he achieve this?

Most of Stossel’s videos follow the same 3-act script:

Act 1: They start with a question or statement about a commonly held fact or belief that Stossel will then look “deeper” into in his five-minute YouTube clips. Often, he pretends to bolster the initial claim by highlighting clips and media reporting supportive of it. He frames it as the “status quo”.

Act 2: He gives voice to a supposed expert or interviewee who disagrees with the “mainstream” perception, a stark contrast. Why would they come to a different conclusion, did we not just hear what the facts are? He then pretends to challenge the contrarian, giving him enough space to introduce decontextualization, motivated reasoning, or other misleading talking points. Then Stossel takes over judgment, highlighting cherry-picked facts or reporting that seems to support the contrarian; ultimately coming to an agreement with him. A nice little “journey” for low-information watchers to follow; a facsimile of an educational moment, but distorted for persuasion.

Act 3: In his conclusory remarks, he or his interviewees re-iterate what we now “learned” by looking deeper. This reinforces the new narrative and prepares watchers for a final “call to action” that usually is in service of Stossel’s ideological position.

If this 3-act structure sounds roughly familiar, this is because it is structured to bring watchers along a powerful story trope called the “hero’s journey”. Stossel’s watchers get taken away from the “status quo” and are brought on an adventure where they meet new companions, challenges, and struggles, to then finally return changed or wiser.

Who does not like to feel they learned something precious, coming home — after watching a clip — feeling a bit like a hero? This type of content and trope is as ubiquitous as it is persuasive, and we fall quite easily for it on any topic we know much too little about or overestimate our competence.

Information asymmetries always exist because nobody can have detailed knowledge about everything. But unless we recognize them for what they are and put our guard up, we will be an easy mark.

A very recent example of such a “Stossel” special journey just went online on a new GOP classic, which is the false myth that COVID-19 was created in a Wuhan lab with the help of “US government” funding.

In the video, Stossel starts laying out the status quo, how US senator Rand Paul accused Fauci of funding the creation of the virus, and how the media all claimed it came from nature and lambasted Rand Paul. Then he sits down with Rand Paul for an interview and lets him air some talking points. Next up, some one-sided media snippets to suggest that we learned there is more to the story. Adding selective quotes from news about the FBI and DoE assessments, reports on how other viruses leaked from labs before, and some decontextualized clips of scientists. Taking advantage of his watchers’ ignorance about the details, he offers example after examples that seems to contradict what the mainstream told them in Act 1. Did they learn now by themselves that Rand Paul was right after all? He certainly judges that to be the case. In Act 3, he lets a magnanimous Rand Paul pontificate about how he does not want an apology, he just wants to prevent the next pandemic by not letting “government research” create these dangerous viruses. What a brave truthteller! Luckily, we who have been on a journey with him and have not been fooled by the “science and mainstream media”, can feel a bit like a hero too. Brilliant!

And self-sealing.

Science has lost at this point. Because all that the truth has left on offer for true believers is a bitter realization.

One where they are not really heroes, but rather have been conned by seasoned manipulators on a topic they knew too little about.

I leave it to your imagination how receptive citizens are to hear that message, especially those already aggrieved with little to feel good about themselves. Most manipulation tactics hold their power on an emotional level, the shticks and spiels are just to provide enough cognitive distraction to get lured into these positions.

Talking about emotions, I heard fear can be quite useful too.

The Slippery Slope Scaremongers

How they work:

A slippery slope argument claims an initial event or action will trigger a series of other events and lead to an extreme or undesirable outcome. However, these arguments are often fallacious because they imply inevitability, causality, and necessity between individual steps. Slippery slope arguments appeal to a mixture of factors such as habituation processes, problems in drawing distinctions, and social pressures in the direction of a slippery slope. (Jefferson A., 2014)

Media manipulators use slippery slope arguments to instill fear or other negative emotions in their audience by presenting (hypothetical) extreme consequences as if they were a certainty. (Nikolopoulou K., 2023) This is a form of fearmongering that plays on humans’ inherent aversion to loss, perceived threats or negative outcomes, sometimes at the expense of logical reasoning (Lerner & Keltner, 2001). Shared fears can also be abused to guide collective behaviors, socially reinforcing individual fears and beliefs about risks (Kasperson et al., 1988).

Case study: Fear-mongering about School-based Health Centers

Getting even basic healthcare is often tricky in the US. School-based health centers (SBHCs) are primary care clinics based on primary and secondary school campuses that would take care of the children’s physical and mental health. While the first SBHCs go back over a century, they have become more popular in the last 30 years because they come with some substantive benefits.

Their biggest impact is on the health and well-being of children with high unmet needs, such as uninsured students or healthcare access disparities among African American and disabled students (Wade TJ. et al., 2008 , Guo JJ. et al., 2010). SBHC have also been linked to lower absences in school and positive academic outcome (Magalnick H. and Mazyck D., 2008). There has been some controversy surrounding school-based clinics that provide reproductive health care in conservative states like Louisiana in the past (Zeanah PD et al., 1996). Yet overall, these centers had a very positive footprint on students and schools that implemented them and thus increased in popularity.

So all good and well, right?

Let’s say their recent success was not liked by everybody, because SBHCs have also been shown more effective than community centers such as hospitals at facilitating preventive health measures including vaccinations (Federico SL. et al., 2010).

By now, you should know exactly where this is going:

Let’s not give these despicable anti-vaccine pressure groups any more air than necessary. The point is that albeit slippery slope arguments are often fallacious, they can still be persuasive when coupled to a very strong emotional cue like fear.

If parents worry about losing the right to protect their children, they will not question whether the long slippery slope argumentation line before them is very probably or sound; they will just reject the initial step immediately.

I guess we all can emphasize. But that’s why it is so important to guard ourselves against emotional manipulation and maintain our analytical capabilities in arguments.

Talking about sound reasoning… there are ways for manipulators to abuse our sound reasoning as well, if only they manage to make us belief in false causal relationships…

The false-cause Fabricators

Narrative tools often operate under the radar of conscious reflection, leaving us with the impression that we have a direct, unmediated picture of reality —Prof. James Wertsch

How they work:

Humans have an innate desire to understand causality. Our pattern-recognition ability evolved to help us understand and predict our environment, but it has a tendency to overfit data to patterns, and perceive connections between unrelated things (Fyfe S. et al., 2008, van Prooijen, 2017).

Media manipulators can abuse this predisposition to prompt us to falsely attribute relationships to events that correlate in time, also known as post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacies.

A related version is the “Narrative Fallacy” (Taleb, 2007) where manipulators take advantage of our desire to shape scattered facts into coherent stories. Collective memories and shared narratives can amplify these false causalities, especially if they align with broader cultural stories or beliefs (Wertsch JV., 2021, Erll A., 2022).

The narrative fallacy addresses our limited ability to look at sequences of facts without weaving an explanation into them, or, equivalently, forcing a logical link, an arrow of relationship upon them. Explanations bind facts together. They make them all the more easily remembered; they help them make more sense. Where this propensity can go wrong is when it increases our impression of understanding [but not our actual understanding].

Case study: The ever-expanding miracle cure illusion

A core strength of medical practice is the trial-and-error strategy of initiating a treatment and assessing a patient’s response. However, this strategy is subject to post-hoc ergo propter hoc fallacies because an observed change in the patient’s health is not necessarily caused by the medical treatment (Redelmeier and Ross, 2020).

The reason to fall into these fallacies are manifold, for example, the placebo effect can complicate the manner. The mere expectation of receiving help and treatment can lead to a positive perception of disease progression or severity while reducing patient suffering after any type of intervention. This does not mean the intervention was effective, to really do that, placebo-controlled studies have to be held.

On top of placebo, phenomena such as regression toward the mean can also create the illusion of causality. Patients are most likely to seek a doctor’s help at the peak of disease or discomfort, but no peak lasts very long (regression). So after a “peak” doctor’s visit, patients will automatically feel slightly better, no matter if the doctor gives a medication, placebo, or just a few encouraging words.

All of the above factors (and many more such as doctor’s expectations, observer bias, and bad statistics) can initially make a drug seem falsely effective, that’s why multiple good studies (such as randomized control trials) are required to really establish whether a drug works or not. But experiencing improvement or having strong hopes can cloud our judgement for a long time.

The history of medicine is full of people believing in false remedies to diseases, and subsequently self-serving manipulators abusing their hope, suffering or confusion.

The literal snake-oil salesmen in the 18th century were SELLING SNAKE OIL as a cure-all elixir, a literal fake miracle cure, for gods sake. Today, within our broken information ecosystems, this type of business continues unabated to trick the unaware. False causality is easily attributed to whatever product they want to peddle, all manipulators need to do is add a bit of narrative flavor to the sales pitch. Anecdotes about how the “supposedly vaccine-injured see profound results”, or how the cure has “won the noble prize” (for it’s actual efficacy, which is parasite-killing, not miracle curing), or how “the pharma companies don’t want you to know about the miracle cure because it would harm their profits” and “hey it might also work against cancer and inflammatory diseases”. *eurgh*

You all know the spiel.

Many media manipulators often gain a hefty income by selling supplements and other dodgy products they tout as miracle cures. Platforms and law makers need to introduce consumer protection mechanisms against these manipulative vultures who prey on the hope of patients.

But how do manipulators deal with scientific pushback when those cures get debunked experimentally? And why would people rather take some dodgy miracle cure against COVID when safe and effective vaccines are available?

Well, let’s check out the next tactic.

The Exclusionary Scotsmen

“I do not have a problem with vaccines, just with the mRNA gene therapies” — victims targeted by well-funded vaccine disinformation

How they work:

When confronted with scientific information that contradicts our beliefs, we experience discomfort and cognitive dissonance (Harmon-Jones et al., 2009). To resolve these contradictions, we often fall into special pleading (Dim Y., 2018) by setting different standards for different arguments to unjustly reject inconsistencies.

Media manipulators can foment special pleading with appeals to purity, identity or moral credentialing of their in-group. By claiming that “no true scientist” would ever act or speak in a dissenting way to their beliefs (Manninen TW, 2018), they aim to assert their group’s moral superiority (Monin & Miller, 2001) and give citizens license to disregard or devalue inconvenient counterexamples.

Level 1: Discrediting inconvenient evidence

Level 2: Discrediting an inconvenient scientist

“I offered to go on Joe Rogan but not to turn it into the Jerry Springer show with having RFK Jr. on” — Dr. Peter Hotez

Dr. Peter Hotez is a vaccine scientist, vaccine advocate and book author. He has developed a low-cost and effective COVID vaccine serving over a 100 million people; a model case for public health without the profiteering of big pharma companies. He also is the father of an autistic daughter and wrote a very personal science book about the genetic determinants of autism, debunking the maliciousness of claiming vaccines causing autism.

Obviously, everything he stands for puts a target on his back by anti-vaccine extremists, even decades before they gained new power with the politicization of the pandemic and our broken info systems. One of the most despicable manipulators, former lawyer and seasoned liar RFKjr. has long labeled Dr. Hotez as the “OG villain”, marking him as target.

When the Joe Rogan Experience — a popular podcast regularly platforming a variety of anti-science contrarians, cranks, conspiracy theorists — gave a platform to RFKjr. and his anti-vaccine talking points, Dr. Hotez shared a VICE article lamenting the blatant misinformation being spread to millions.

His indirect criticism still prompted the entertainer to angrily challenge Hotez to a debate with RFKjr., to be moderated by Joe. Basically a public mud fight over a topic only one person is qualified to talk about. Unsurprisingly, Hotez disagreed at the prospect of inviting any false equivalency between him and the malicious RFKjr. Nevertheless, he offered Joe Rogan to come on the podcast to explain to him point by point why RFKjr.’s talking points were wrong.

Joe Rogan agreed and a nice and well-informed conversation ensued…

Of course not. Hotez polite refusal was immediately seized upon by Joe Rogan and many anti-science actors to attack and discredit him. With so much attention, even the spitefully foolish owner of X/Twitter took it on himself to pile-on and stoke the toxic flames of harassment. The consequences were predictable:

Is this really the way we should treat public health scientists that work tirelessly to help countless people for little money? Getting railroaded by “debate me bro” podcasters in service of shameless liars whose actions have caused incalculable harm? And is a podcast discussion even a debate, or rather cheap showmanship?

Scientific debates, even on the most controversial topics, constantly happen in science. But their format is scientific papers that make arguments based on data and analysis, not bravado and rhetoric. Scientific debate is slow, meticulous and a much less entertaining process than a podcast shouting match. But there is a good reason for this: Nobody can debunk all bad arguments and falsehoods of rhetorically media manipulators in a live debate. Studies after studies have shown that if you pair a domain expert with a manipulator in a debate format, false equivalency ensues and people will still end up misinformed about the topic at hand (Imundo & Rapp, 2022).

There just is nothing to debate between fact and fiction, and even if one could debunk the arguments on the fly, skilled debaters just keep moving the goal posts.

The time and effort to debunk falsehoods is at least an order of magnitude higher than it takes to just make them up.

And that is even before considering the “pleasantness” of having Joe Rogan and RFKjr twist your words into strawmen arguments to validate the beliefs of their tribal audiences.

Guess that brings us to the next tactic in the manipulator’s arsenal.

The strawmen architects

How they work:

We have an innate tendency to view members of out-groups as more similar to each other than members of in-groups (Quattrone & Jones, 1980, Judd et al., 1991). We also judge probabilities through a representativeness heuristic by comparing an event to a prototype or stereotype that we already have in mind (Gilovits & Savitsky, 2012, Balia S., 2015)

Media manipulators play into these tendencies by treating the complex positions of out-group members as if they are monolithically simple and representative of a flawed or extreme stance. These oversimplified strawmen arguments are more easily processed (Kahneman, 2011) and can be pompously debunked to persuade and reinforce “in-group” solidarity (Harwood J., 2020).

Case study: Climate change action is just another word for genocide

“All of that reeks to me of and underhanded and brutal genocidal impulse” — Jordan Peterson’s strawman about environmentalism

Alex Epstein is a climate change denier, propagandist writer and messaging consultant for fossil companies. He recently published a book advocating for the expansion of fossil fuels and is now touring rightwing networks for promotion.

Logically, when such a seasoned climate denier and manipulator like Epstein comes together with pathological drama queen and galaxy-brain bullshitter Jordan Peterson, any tethering to reality goes out the window.

Among the many obvious and dated strawmen the two heat up for their tribal audience, one absurdly flawed line of thinking particularly seems to stand out:

“Any action against fossil fuels is inextricably part of a genocidal de-population agenda.”

Conspiratorial issues aside, this ridiculous characterization of their opponents position is of course not build on a single strawman argument, but a whole barn-fire full of them. Here is a rough outline:

“The climate catastrophe movement has a total non-interest in the obvious biological productivity benefits”

“That is because environmentalists believe that any type of human impact on the planet is bad”

“Their metric is the purity of the planet, not human well-being”

“But if they believe all humans do to the planet is evil, then the solution is obvious: Better to have a hell lot fewer of us”

“They have this view on humanity as some kind of cancer. We are not yeast in a bloody Petri dish. The planet is not a Petri dish”

“Every single bit of that reeks to me of an underhanded and brutal genocidal impulse”

Now most people realize that the two of them just talk total nonsense, arguing against figments of their own imagination. However, the goal of strawmen arguments is not to convince people for the cause. The aim is identity justification and tribal mobilization. Once believers are activated about the imminent danger of environmentalists and their supposed “anti-human” depopulation agenda… time to sell them stuff for supposed safety or comfort.

Ultimately, strawman arguments just serve to keep citizens trapped in ideological, tribal or social groups, and leaders who use them usually have ways to profit of them, politically, financially or socially.

Talking about tribal identification, I wonder if there is another lever manipulators can pull to stir us towards their ends?

The Ad Populum Propagandists

How they work:

We often do things because many other people are doing them, regardless of our own beliefs or supportive evidence. This bandwagon effect (Bindra S. et al, 2022) is innate to social beings influenced by pressures and norms of groups, from wisdom of the crowd (Suroweicki, 2004) to social proof (Cialdini, 1984).

Media manipulators abuse our tendency to look to others by appealing to the popularity of an unsubstantiated position (McCrew BW., 2018) or taking advantage on the individual’s fear of being isolated or ostracized (Williams KD et al., 2022).

A related tactic is to invoke common practice or tradition to assert that a premise must be right because people have always believed or practiced it (Michaud N., 2018).

Case study: The silent majority has spoken, evidence be damned

A common trope of pundits and media manipulators is to use polling data to spin narratives, justify their beliefs, or advocate for political action.

Representative polling is often hard to come by, and many of those pollings should be taken with a grain of salt. Nevertheless, while polling has (and ought to have) some legitimacy for politics, what a majority of non-experts believe is entirely irrelevant to science.

The validity of a scientific theory is based on evidence, plausibility, and coherence with existing knowledge (among other things), but not popular appeal. Nor can a dissenting popular opinion negate the broader scientific consensus on any well-established or emerging scientific topic of inquiry. Scientific reality is what does not go away even when people stop believing in it.

Almost everybody agrees with this. And yet, we seem to forget when skilled media manipulators frame scientific questions as a political our tribal issue, to be decided by a popularity contest.

What the “majority of Americans believe” has not only shifted over time, it also tends to fall on the wrong side of scientific knowledge when media manipulators are at work. No matter if in the past with Darwinian evolution and Climate change, or more contemporary with vaccines and SARS-CoV-2, popular sentiment can take wide swings independent of evidentiary basis. And while citizens are entitled to their opinion, I believe society can only prosper when decisions are made according to the best available science.

In the information age that asymmetrically favors falsehoods over science, popularity has become a dangerous proxy for truth.

That brings us to a final concluding remark.

Concluding remarks

Something went awry in our information sphere, and not just during the pandemic.

We went from information scarcity to information abundance and ubiquity. We went from mostly being an information receiver to being a constant broadcaster of it. We went from careful curation and gatekeeping to free-for-all cage fights for our attention. Clickbait, memes, hacktivism, virtue-signaling, community raids, micro-targeted persuasion campaigns, crypto scammers, conspiracy myth entrepreneurs, synthetic media, bot networks, astroturfing, unrepentant information warfare. All these and more now happen — and often define — what most citizens get to see in their fragmented digital spaces.

The merciless and bloody winner-takes-all fight for our attention has somehow transformed the traditional role of information in society: To inform and educate us.

Media manipulators thrive in the battlespace of information. They do not share information to educate us. They tell us whatever we want to hear and what keeps us engaged, but not necessarily what we ought to know. Truth is often an obstacle to attention-grapping stories, but fictions can be tailored and optimized for their niche audiences. Many media manipulators selectively amplify information that furthers their ideological, strategic, or financial goals. Largely unaccountable, they share information in service of popularity, persuasion, profit, or power, not the public good.

Media manipulators have set their sights on one of the last bastions of evidence-based reasoning in society: Science.

Evidence, research, fact checks, debunking, and scientific literacy are a threat that undermines their business model, popularity, and power. Media literacy, scientific knowledge, and critical thinking are a type of immune defense that allows civilians to arm themselves against their manipulation.

And believe me when I say: They rather not have you inoculated

I chronicle and explain their tactics because I believe much of the doubt, ambiguity, and confusion surrounding scientific topics, institutions, and ultimately scientists today did not arise organically.

Instead, it was fostered by deep-pocketed anti-science networks and the collective actions of media manipulators online who rather have science take a backseat in public discourse and societal decision-making.

The bitter reality is that currently, manipulators are winning the war for your attention, for your money, and ultimately for your agency.

Are you really going to let them get away with it?

I’d say the buck stops here, right now, with you.

Good luck.

To make our odds of success a bit higher, here are 5 templates in high resolution to equip you to fend off manipulation on 5 popular anti-science topics. All are free-access and free to use, share, build upon, and so forth. I just ask you to properly attribute (Creative Commons CC-BY-NC 4.0).

Disclaimer:

This article, like the previous ones, hold the dilemma that they might be used by bad actors as a guide on how to influence or derail discussions.

I just wanted to share a few considerations about why the benefit of writing about them outpaces the risk:

Ubiquity. These tactics are already widely used, many of them as old as time. My article highlighting why they work is unlikely to dramatically increase their use.

Harm reduction. It is my belief that these tactics mostly work to manipulate when there is a lack of awareness. Creating awareness thus should reduce harm, especially around medical discussions.

Combatting side effects. These tactics create noise pollution, and noise pollution comes with many societal diseases we yet have to wrap our heads around, like epistemic paralysis, nihilism, and conspiratorial thinking. If enough people come around to see the bigger picture, systemic changes to our info spheres are more realistic.

Restore agency. Manipulation robs us of a fundamental human right, the freedom and agency to make our own decisions. There is no democracy when citizens have no agency.

As always, my hope and goals are to educate and equip citizens with conceptual tools and new perspectives to make sense of the world we inhabit.

This article took a lot of time and effort to conceptualize, research, and produce, actually almost irresponsibly so given that I do not monetize my scicomm and certainly do not plan to start with it now.

I see this work as a public good that I send out into the void of the internet in hopes others will get inspired to act.

You are also invited to deepen this work or just derive satisfaction from understanding our chaotic modern world a bit better.

The first question when evaluating any assertion, couched in any terms, is "how do we know that?" It is one question that must be asked twice; the first time with emphasis on the word "how," the second time emphasizing "know."