Exclusive: The inside story behind the search for the origins of COVID-19

A big screen documentary movie, an announcement, and an exclusive excerpt from "Lab Leak Fever", the definitive book unraveling the pandemic origin controversy

Image credit: Emile Ducke

So it has gotten quiet around here because I have been working for years on two big projects to resolve the COVID-19 origin controversy for ordinary citizens.

The Movie

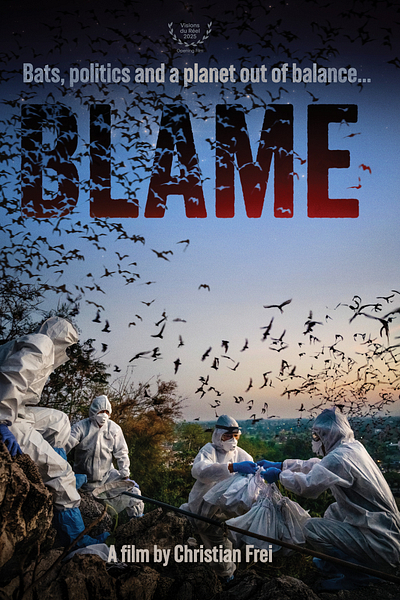

The first one is a big cinema documentary movie directed by Oscar-nominated Swiss Filmmaker Christian Frei called “Blame: Bats, politics and a planet out of balance”

When Christian Frei approached me in March 2022 about participating because he read my article about the topic, I was not sure if I was being pranked. But then we met and I realized that he was somebody who tried to really understand what happened, to those scientists, to science, and to all of us in this traumatic pandemic.

The Book

In early 2023, I decided that I wanted to tell the real full story of the origin controversy. Until then, I had been incredibily lucky to interview many key scientists involved in the search for the origin of SARS-CoV-2 and learn enough of the science to understand the full body of evidence and the scientific consensus arising from that evidence.

What I did not understand was how public opinion was so far from scientific reality, so that is what I began to investigate. In each chapter of my book, you will not only find unheard testimony and unique insights of scientific protagonists, but also hear about the many surprising obstacles, antagonists, or tormentors in our modern information ecosystem that sabotaged their work and our public understanding. These range from cynical anti-science activists to profiteering influencers, from social media trolls and conspiracy theorists to contrarian experts, motivated journalists, sitting US Congressmen and Senators up to the US President and the Chinese Bureau of State Security.

United by a common scapegoat, their loose alliance of connivance and calculation seeks to gain popularity, profit, or power by keeping the scientifically unsubstantiated but emotionally satisfying lab leak hypothesis alive. Their actions and agendas expose how the technological disruption of our information sphere has created new vulnerabilities in our social fabric. In turn, these vulnerabilities are constantly exploited by a new class of power holders in our midst: influencers, platforms, and online crowds… it was quite a ride.

The book should have been published in early 2025 in the US, but then Trump won the election and the risks became too high for my publisher. I was not intending to speak about this, I thought the book was dead. But then the German intelligence agencies began seeding a lab leak narrative through shady methods in the German-speaking sphere, so I had to act, no matter the risks to me personally. And the risks for telling the truth are real, unfortunately. So I spoke about this with de Volkskrant, a renowned newspaper in the Netherlands.

I am sorry for my many American and international friends that I can currently not offer the original English version due to geopolitical sensitivities and very real dangers to become a target of powerful actors, in China, and more worryingly, in the US. But I will give you an exclusive excerpt to form your opinion about why this book going to change the false lab leak narrative forever, and what I learned about the media manipulators in the back.

As one of the few, if not the only western writer, I got to interview George Gao from the Chinese CDC and Zhengli Shi from the Wuhan Institute of Virology. What did they do when a pneumonia of unknown aetiology broke out in Wuhan?

Let´s find out:

Disclaimer

This book is told from the perspective of multiple scientists and the author who recount the events surrounding the pandemic origin controversy to the best of their knowledge.

Chapter 2: Early Drums of War

I tried really hard to never say anything wrong.

- Dr. George Fu Gao, Director of the Chinese CDC

We believed the results. But I could not believe the results, you know? That was not possible. We always said, “Oh, one day it will come,” and it really came.

- Prof. Shi Zhengli, Wuhan Institute of Virology

“Without a harmonious and stable environment, how can there be a home where people can live and work happily?”

Xi Jinping's words on New Year’s Eve in 2019 were intended to reign in pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. For months, the city has been in a renewed battle for its soul against the oppressive and subversive influence of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, were expected to march again on January 1, 2020. The goal was to maintain political pressure after a landslide victory of pro-democracy candidates in district court elections weeks prior. Six thousand police officers were deployed to deal with potential unrest—the wrong signal to send, given previous escalations and excessive police brutality. “Safety concerns” led to the cancellation of the midnight fireworks despite months of planning. The next day, a peaceful protest with families, kids, and the elderly, often dressed up in costumes, quickly escalated into violence, tear gas, and mass arrests. The police blamed some radical student agitators who had hijacked the march. Maybe it was inevitable; tensions had been high for months. Universities and their students were front and center of the recent civil rights movement, and the police claimed these institutions had become “weapon factories.” As a result, sieges and raids on universities have become part of campus life over the last few months.

The last thing the exasperated Jasnah Kholin (pseudonym) needed at the time was “one more fucking thing to worry” about. The unfiltered coronavirus researcher (who swore like a sailor) now uses a pseudonym to hide her real identity for safety reasons (I promised her that I would omit any details that she felt would compromise her safety). She, like many others, had been at these protests for civil rights and experienced firsthand how they were squashed by the police, often with force. Once, the young academic had a pepper ball barely miss her face that would certainly have knocked her out. Another time, the police came to pick her up, and she was in prison for weeks before they let her go. Wrongfully suspected or not, she was among the lucky few who got out uncharged because there was no evidence to place her at the scene. It’s not surprising she had an innate distrust of the Chinese authorities, who were more and more entrenched in Hong Kong, her only home.

When she heard about the pneumonia outbreak in Wuhan around New Year's on ProMED-mail, an internet service supported by volunteers that tracks unusual health events, she immediately started screenshotting and saving every bit of information that was coming out of Wuhan: every pdf, every Weibo message, every picture, all kinds of vital info. Because of Chinese censorship, information can sometimes be lost within minutes of appearing online. What foresight! “Oh, I am very familiar with how information works in China,” she would later explain to me. In any crisis, Chinese authorities shut down the information flow to try to control the narrative. This is not unusual; it happens for things big and small, important or insignificant. This approach might even help to contain false and harmful rumors during a crisis. However, it also creates a layer of obfuscation and political spin that can make it challenging to assert pertinent facts with any confidence. For example, consider how dangerous the virus was and how it spread. In the very beginning, the Chinese authorities claimed that the virus was barely, or not at all, transmissible human-to-human in an attempt to not cause panic, a claim that was still being repeated by the World Health Organization (WHO) on January 14th.

Jasnah Kholin and her academic colleagues in Hong Kong did not believe any of it. They had been burned before. On January 4th, Jasnah caught wind of a concerning story on Weibo (Chinese Twitter) about an infected father who had not gone to the Huanan market. Chinese censors deleted it within the hour. Yet for her, already gathering as much from rumors, the specifics of this story were the final indication of human-to-human transmission, vehemently denied by Chinese authorities until weeks later. Many other coronavirus experts were just as suspicious as her, including SARS-veterans Yuen Kwok-Yung, a giant among Hong Kong's infectious disease experts, and Leo Poon, who developed the first PCR diagnostic for SARS in 2003. They all independently read the signs on the wall and raised the alarm in Hong Kong about the human spread. “SARS was a generational trauma for Hong Kong; this was not our first fucking rodeo,” Jasnah kept cursing. According to her, SARS-1 had also been much closer to a pandemic than people commonly realize. However, all of them knew this and did everything they could to make the rest of Hong Kong take this seriously.

Most likely, their actions at the time helped the city avoid the worst. By any measure, Hong Kong's early and harsh response has been a success story. With the high uncertainty and unclear messaging from mainland China, it fell mostly to outbreak professionals and coronavirus academics like Jasnah to exert caution and inform society. Speed is everything in emerging outbreaks; the longer it takes to mount collective action, the worse it usually gets. Because of their warnings, both the population and Hong Kong’s chief executive would take the threat seriously and implement strict pandemic prevention protocols. From the first to the fourth wave, Hong Kongers succeeded where most of the world would fail; they suppressed community transmission of the virus.

Yet not everybody was happy. Pro-democracy protests saw their momentum decline under new restrictions. They were especially concerned about the ubiquitous use of contact tracing and digital surveillance, which they feared would be a new and powerful tool in the hands of the police. In the following months, civil rights protests were canceled, and the CCP exerted even more political pressure on Hong Kong. Stuck between a rock and a hard place, Jasnah, like many in the wider Chinese diaspora, wished that somebody would blow the lid off this thing in those early days. Why did the CCP initially deny the obvious human-to-human spread? Why the silencing of doctors? Did the communist party really think they could hush up the severity of the outbreak? When will the world wake up about the Chinese government? Somewhat ironically, the tumultuous cultural and political moment, along with this appropriately placed mistrust, made the Chinese diaspora, especially Hong Kong, very susceptible to a different type of viral spread.

Since December 30, when the outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology became official, sporadic voices both on Chinese and Western social media have put the connection of WIV’s biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) laboratory into public spaces, albeit in the context that they had the capacity and expertise there to handle the outbreak. The positive connotation did not last long. Within five days, this information would be presented by a pro-civil rights protester in Hong Kong to suggest quite a different connection. A tweet from the time, still visible today, reads:

My guess is China has ordered an attack on Hong Kong with bio-weapons to stop the continuous protests. Like in 2003, the CCP assisted the outbreak of SARS in HK to pave the way for #CEPA. You can't underestimate how evil this regime is. #Bioweapon

Others echoed the idea, highlighting the particular timing right after the New Year’s protests that ended in violence. While none of these rumors gained any wide-reaching traction, they symbolized both fear and suspicion about the CCP and what they would or would not do. Suspicion was warranted. Independent information from Wuhan was hard to come by. And ordinary people would never get the full story.

Many of the early outbreak threads come together in one person, Dr. Gao Fu, known in the West as Dr. George Gao, director of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC). Within China, public health authorities like the CCDC had mostly independent community-level, state-level, and federal offices, and George was sitting at the top node where all data would cascade towards, in many ways, the highest public health position in the land, only below the communist party’s National Health Commission. Dr. Gao rarely gave interviews, and every time he did, he would be investigated by authorities. The Associated Press learned of three such instances. When I managed to get an interview, it was a random Sunday afternoon. He was still in the office, working alongside his personal assistant. He kept running out of our interview on and off, dictating instructions in Chinese under his breath, sometimes even while I was directly talking to him.

Originally a veterinarian, George went to Oxford for a PhD and postdoc in Virology. After that, he went to Harvard for a few years, then back to Oxford as a group leader, before returning to China and starting his meteoric rise. From the Chinese Academy of Science to heading National Key Laboratories, working on the ground in the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone (his role was described as “heroic” by the US National Academy of Science), and all the way to becoming the Director of the Chinese CDC. By any measure, Dr. Gao is an incredibly successful scientist and possibly an equally skilled political tactician.

Most of our conversation was not about the questions I asked but a mixture of highlighting the work he has done, the papers he has published, the awards he has achieved, and overall, how great China did. “I have been on the frontline from the very beginning for the vaccine development in China, and also, I have some original publications for antibody development,” he said as he rattled off a long list of things I did not ask about and that went quite beyond the scope, but soon I would figure out why. He used it as a preamble to say that writers like me should really write for the general public about his and China’s amazing achievements. He jumped up from his chair to show me popular science books he had written in Chinese, and if I was interested in writing about these topics, we could write something together. I was torn between rolling my eyes and staying diplomatic. What a start, I thought, not even five minutes into our conversation. It went a bit better when I prompted him to put down a timeline for the early outbreak.

By the end of December, there were already rumors of another SARS outbreak on the Chinese internet. People were getting sick, and some doctors discovered that their patients had an association with the Huanan seafood market. Perhaps even market visitors or vendors noticed something unusual and spoke up as well; reconstruction has been difficult. As far as anybody can tell, these speculations started only around the last week of December but would soon harden into alarming action.

On December 30th, the municipal government issued a “red head” letter—an official document—noting they had a PUE (pneumonia of unknown etiology). The letter asked that if any other hospital notices similar cases, take them seriously and report them to the Bureau of Health. When Dr. Gao read that, he sent his staff and second-in-command to Wuhan. On December 31st, they collected samples from hospital patients.

On January 3rd, they got the first sequences confirming it was a coronavirus. In parallel, they quickly developed PCR primers and sent them to the local CCDC in Wuhan so they could start testing and screening patients. He could not stop himself from mentioning how China did well in contrast to the United States, where officials struggled with developing their own PCR test, which was a bit of a scandal at the time under Robert Redfield’s CDC. On the 5th, Gao and his team were trying to isolate and culture the virus in all the cell lines they had. They even took lung tissue samples from acute patients. “We were prepared to try everything, but in the end, this particular coronavirus was so easy to grow,” he admitted. On the evening of the 6th, they saw the canonical picture of the coronavirus (the spikes around the viral particle that look like a crown) under the electron microscope. This would famously be published in The Lancet, a renowned medical journal, a few weeks later.

On January 10th, Dr. Gao would personally visit Wuhan. They would report the first fatal case a day later, on the 11th. The following day, Gao’s team had been taking environmental swabs from the Huanan market multiple times, a place epidemiologically linked to most early patients in the hospital. However, the municipal CCDC in Wuhan had discussed shutting down the market on December 31st late into the night, and on January 1st at 8:00 a.m., fully geared CCDC workers would disinfect it. “So, there was not much to see anymore,” George told me. Yet neither official source acknowledged human-to-human transmission.

Dr. Gao traveled back to Beijing only to return to Wuhan again a week later, on the 17th, with another expert committee to assess the worsening outbreak. By then, he told me, they all felt that this outbreak was very serious. Many healthcare workers were getting sick, too. In full PPE gear, Gao’s team would interview patients and doctors, whereas he would personally interrogate the directors of the various hospitals with coronavirus cases. They had to make an announcement. “We were always discussing when we should make this official announcement. We didn't want to create a big panic; we wanted a chance to get the disease done.” It was a difficult balance to strike, given the rumors at the time. “I never spoke to the media before the 20th; because I am the director of the CDC, I cannot speak out without evidence… But we felt and we thought it was human-to-human transmission, but we need evidence [sic].” He was right; no matter if it is the Chinese CDC, WHO, or any other organization, scientific evidence is always much slower to come forward than speculations and rumors. When I asked him how he felt about this asymmetry, he finally dropped some of the self-promotion and got angry. “With all these conspiracy theories, what can you do as a scientist? You cannot do anything. All you can do is keep yourself quiet. Can you argue? You wanna quarrel with them? Fight with them? In the media? You’ll never have the end.”

In the months following January, Dr. Gao had been fiercely criticized for not announcing human-to-human transmission earlier, so I guess he felt the need to keep reiterating how he had always considered that there was human-to-human spread. It was a coronavirus, after all. That it would spread between humans was never in question. But how much? “MERS did not spread well between humans,” he offered as another example. One really needs evidence to substantiate and classify claims. “I tried really hard to never say anything wrong,” he defended himself. After that, he went on another round of deflection— “Americans and Europeans would not even wear masks” —and more self-promotion.

I asked him how he dealt with the pressure and never-ending criticism. “I don’t want to be in the spotlight, but it comes with the position; people put you in this position. If I did something wrong in the last three years, I cannot change history. If you tell me, ‘George, you did this or that wrong in 2020,’ … I know we have some lessons to learn, but that is not our Chinese culture to say. We only say we learn experiences [sic], not learn lessons.” He pointed out how the Germans officially admitted to the mistakes of the Second World War, but the Japanese never did. Any admission of failure comes with the threat of losing face. Being silent was a way to preserve it. “We never use the word ‘lesson’; you guys can use lesson.” He chuckled a bit at this cultural idiosyncrasy—maybe the one thing that was truly coming from him as a person, not him as a political tactician. He spent fifteen years living outside of China and was trained at Oxford and Harvard, he reminded me. He believed that he understood both cultures and that understanding had equipped him for his position. “If it were not me, with such a big pressure, the world would be different.” He reiterated this last point twice. I think he was correct, but whether it would have been better or worse if a less skilled politician had been in his influential role remains open to interpretation.

The simple fact is that while Chinese scientists were well positioned, Chinese authorities had failed to learn some crucial lessons from the original SARS outbreak. They tried to control the message before the outbreak overwhelmed them. On January 3, 2020, after a week of rumors about a new SARS outbreak appeared on social media, a memo from the National Health Commission, one of China’s executive departments of the State Council, ordered the shutdown of all outbreak communication. Digital censors would filter and delete messages talking about the outbreak from Weibo, websites, and anywhere else online. In a situation where speed of communication is everything, artificial barriers to information flow can be a poisonous thorn. Even Chinese scientists were not allowed to talk to the press or release any data in an effort by authorities to keep a lid on this thing until they could figure out how to spin it. The authorities muzzled them and prohibited them from speaking with outsiders, at least in theory. Is it really any surprise that the rest of the world was suspicious?

There were rays of hope, though. I believe one has to understand that science is not only an engine for innovation or a way to get fancy new gadgets but has always functioned as a tool of global diplomacy. Even during the Cold War, scientific collaborations and trust built between researchers would often circumnavigate political nonsense. The Wuhan outbreak was no different. Despite the muzzle, information would be disclosed to academic collaborators. That is why many scientists in authoritarian countries will always be viewed with distrust by their own governments. They fear that a scientist's loyalty to the truth is higher than their loyalty to the state. For Chinese scientists, working under these conditions was, and certainly still is, a difficult line to walk.

Few understand this better than evolutionary virologist Edward Holmes. The British-born scientist, who prefers to go by Eddie, holds a position at the University of Sydney in Australia, where studying viral emergence has been his career and life. In 2012, he became interested in working on emergent diseases in China and struck up several collaborations all over the country, including in Wuhan. One of these collaborators was Professor Zhang Yongzhen from the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center, formerly of the CCDC as well. The two shared many common interests, including discovering novel RNA viruses and studying their evolution. Both saw the potential and power of metagenomic sequencing, a technique where all DNA or RNA sequences from within an environmental sample are amplified without bias. Metagenomic sequencing creates terabytes of data, and filtering through billions of genetic puzzle pieces while trying to stitch them together into novel and unknown genomes is a computationally challenging task that requires expertise, resources, and, of course, local collaboration to get relevant samples.

This hunt for relevant samples brought the two of them to Wuhan in 2014, where researchers from the municipal CCDC took them to the Huanan market as an example of where spillovers might happen. It was no secret that wildlife was sold there, often without the right permissions. Eddie snapped photos of caged raccoon dogs, potentially sick and held in cages in the corner of the western side of the market in unsanitary conditions, with other wildlife stacked below and above them. Eddie had always been interested in the animal-human interface, whereas Zhang was more focused on human pathogen surveillance. That is why the two also visited local hospitals. Zhang had an ambitious vision. He wanted to build a network of hospitals all over China that would collect samples from patients with respiratory symptoms and send them to him to search for new viral pathogens. Where better to find novel RNA viruses of relevance than in the obscure pneumonia cases all larger hospitals see but rarely resolve?

In the end, Zhang would manifest his human-centric vision of an alarm system for pneumonia cases. A system that would now deliver the first patient samples from Wuhan on January 3, 2020, to him. By January 5th, reportedly after 40 hours of straight-up work, team member Chen Yan-Mei had produced the first full genome sequence from these patient samples in his lab. It was a new SARS-related virus. Zhang raised the alarm with his contacts in Shanghai’s Health Authority and uploaded the new viral genome to Genbank under an embargo. “We wrote the paper in two days,” Eddie would later explain to me. On January 7th, they submitted a paper to the scientific journal Nature.

There was incredible urgency to be quick from a public health perspective, but we would be remiss not to note the prestige that comes with publishing. Zhang wanted to get the sequence out, but other Chinese groups, including George Gao’s CCDC and Shi Zhengli from WIV, were also trying to do so, and they had their genomes ready around the same time. The problem was the National Health Commission’s ban on releasing any data. For days, Eddie was urging Zhang for permission to release the genome, but the rules were clear. Zhang was likely torn from what I could gather. It seems to me that when Zhang visited Wuhan in person that week and saw the full scope of the emerging outbreak starting to overwhelm hospitals, he believe word needed to get out. An editor at the journal was pushing him to release the genome, and when Eddie called him when he was on his flight to Beijing, urging him once again to release the genome, he agreed. Zhang’s day had been as eye-opening as it was grim. “Eddie, I authorize you to release the data,” Eddie recalled their exchange. Fifty-two minutes after Eddie received the FASTA file containing the genome sequence, he released it on Zhang’s behalf to a virological website. It would become the global reference genome named Wuhan-Hu-1, the wild-type original SARS-CoV-2. The world would finally get to see the new virus.

And not a second too soon because just two days later, Thailand would report the first infected patient, identified by none other than Supaporn Wacharapluesadee, the Thai virus huntress I met in Chonburi. This alarm from the international spread put pressure and attention on the Chinese authorities to acknowledge human-to-human transmission, which they still had not confirmed with WHO.

Because of his decision to share data transparently, Zhang was named the “saving grace” of the pandemic by Time magazine, and the scientific journal Nature featured him in an article titled “Ten people who shaped science in 2020.” However, his actions were met with scorn and punishment inside China. The National Health Commission had previously reprimanded him with a “rectification” order, temporarily disallowing his team to study the virus. Officials came to “inspect” his lab based on bogus claims about biosafety protocols. They were there to put him on a leash. Silence would fall around him.

Since then, Zhang has consistently denied being reprimanded, reportedly arguing that he did not believe China was controlling information and that their response was simply based on caution due to false statements made by scientists about the first SARS outbreak. “Zhang is now not the same person as I knew him before,” Eddie shared with me. Years later, the ongoing conflict escalated publicly again, leading to Zhang and his team's sudden eviction, which caused him to stage a protest. Dramatic pictures showed him sleeping in front of his office door with policemen surrounding him while students spoke up on his behalf, to no avail. In Eddie’s opinion, the authorities had long punished Zhang for disobeying the muzzle order; his eviction marked the end point of a four-year prosecution, even though he was not privy to the details.

There was also friction with Zhang's release of the virus genome from other sources outside the health commission. In particular, Dr. George Gao from the CCDC felt someone had stolen his prestige. He had uploaded the first genome sequences from his patient samples to GISAID on January 9th (although Gao told me it was the 8th), and they were released by the 12th, a good day and a half after Eddie posted Zhang’s work. Zhang was the first, not him, because he broke the rules. Since then, Gao has used his power and influence to try to rewrite history, striking up a deal with the now controversial Peter Bogner and the database GISAID to retrospectively change the release date to January 10th so he would be first. Others also reported how GISAID bullied scientists into citing the bogus date on the GISAID genomes and removing citations from Zhang’s genome. Everything to create a thin paper trail to make it look like Gao and GISAID were the first.

In reality, neither Gao nor Zhang were truly the first.

On December 25th, the private sequencing company Vision Medicals, a sequencing service provider working with hospitals, had sequenced samples from a retired 65-year-old deliveryman who used to work at the Huanan seafood market and still spent a lot of time there. He was first admitted to Wuhan Central Hospital on December 18th. When a technician by the name of 小山狗 (Xiǎoshān Gǒu, or “Little Mountain Dog”) came to work on the morning of December 26th, she found that her software had flagged a few sequencing reads as belonging to a “sensitive pathogen,” something that seemed like a SARS coronavirus. “Feeling anxious, I quickly checked the detailed analysis data in the background and found that the similarity was not very high,” she would later write in her blog. She initiated a more detailed analysis, finding an 87% similarity to a bat SARS-related virus. But bat SARS are still classified under SARS, so she was worried and compared it to all published SARS-related genomes. She found the closest two—bat-SL-CoVZC45 and bat-SL-CoVZXC2—sampled in 2018 in Zhoushan, Zhejiang Province. They would not remain the closest known relatives for long.

Dr. Shi Zhengli, now better known as “The Batwoman,” had been contacted by her boss at WIV around ten on the night of December 30th while she was in Shanghai for a meeting. Doctors from the Jinyintan hospital had reached out to WIV because they had nine patients with pneumonia of unknown etiology; the suspicion was SARS. Zhengli contacted students in her lab that same night; luckily, three of them were still working. She asked them to stay the night and test the samples. They ran a pan-PCR test for general coronaviruses, as well as a few qRT-PCR probes more specifically for SARS-related coronaviruses. Four and five patient samples tested positive, respectively. “We believed the results. But I could not believe the results, you know?” she recalled for me. “That was not possible. We always said, ‘Oh, one day it will come,’ and it really came.” Her lab was working with coronaviruses; could this be one of the viruses they were working with? She described to me how she felt upset, her hand waving up and down in front of her body. At first, they could not get the full genome sequence, so they could not compare it with what they had in the lab. Only by lunchtime could one of her colleagues get a hold of the virus sequence that Little Mountain Dog had assembled via a hospital sample. The new virus was nothing they had ever seen, isolated, or worked on. “So I feel relieved,” she admitted. No scientist takes lab safety lightly, and Zhengli, who was trained in the West, was no different. But she, like everybody else, has never encountered this novel virus before.

That being said, her extensive work on collecting bat samples paid off. Within her database, there was a pretty close match to a bat coronavirus her team had collected in Yunnan, Southern China. It was a big deal, pointing to the origin of the new virus being bats again. Soon, she would publish the genome sequence extracted from that bat fecal swab, named RaTG13, and with its publication, her troubles would begin (more on that later). Back in the first days of January, her team also managed to sequence the full-length genome of the novel virus from the patient samples the hospital sent them. Zhengli was very proud of her team because they got the full genome, even with the very last base pairs at the end—the trickiest part of the assembly. Her genome sequence was the cleanest with lots of read support; a fact she would be really proud of.

To sum up, within a week of clinicians raising the alarm, three different labs and one sequencing company had identified and sequenced the novel virus causing sickness, which I personally find rather impressive. Even today, there is a broad agreement that nobody had ever seen this novel virus before, and there was a collective effort to identify, sequence, and understand what was happening to patients in Wuhan hospitals. Most Chinese doctors and scientists did their part to quickly help decision-makers have good information for dealing with the outbreak. And yet, upholding appearances and hierarchical politics seemed to somehow have thrown sand into some of those efficient gears. Limiting the free flow of information, muzzling what scientists can say and to whom, and trying to downplay rumors and control narratives slowed down our collective understanding. Much of that continues to this day. Some Chinese scientists get punished for breaking these rules; some do the best they can within the system, and others try to navigate it to their advantage.

In my interview with the accomplished Dr. Gao, getting all the credit for “being first to publish the genome” counted more than sharing pesky details and messy efforts from many scientists to identify and understand this new virus. After his shenanigans with the GISAID database, today he would turn around and claim that because a journal (The Lancet in this case) quoted his GISAID genomes as being the first, it proved that he was indeed the first. After a tedious interview, I felt very little desire to stroke his ego, so our conversation dried up. Either way, he was a good reminder of how personal ambition and politics can tempt even very accomplished scientists down the wrong path of fiction and falsehood. In the larger picture, Dr. Gao’s petty attempts to rewrite his role were a rather mundane quibble left for the history books, inconsequential to how we understood the novel threat. Few citizens of the world had any idea what a way-less accomplished scientist might do when faced with the tragic outbreak of a novel virus and the opportunity to become famous.

Dr. Li-Meng Yan is our first example of one such scientist. Scarlett—as Jasnah Kholin would call her former acquaintance from Hong Kong University by her Western name—was a rather unremarkable postdoc. Yet, in just a few months, the black-haired woman with the square glasses and monotonous, almost robotic voice would leverage her scientific affiliations into stardom. Dr. Leo Poon, a viral disease expert whose excellent lab develops diagnostic tools, hired her in 2015 to conduct experiments with a hamster animal model system to evaluate some of the diagnostic tests the lab was investigating. I tracked down the soft-spoken professor because I wanted to know who Scarlett was before she became a media sensation. Leo explained his lab's focus and that Scarlett had been a hard worker. At the time, her experimental work was focused on studying influenza virus transmission and testing attenuated influenza vaccines in mice. Until January 2020, Scarlett had never even worked with coronaviruses, according to Leo.

“I had no idea what she was up to,” he would tell me. Leo Poon, like other Hong Kong academics, had been preparing for the worst early on. In 2003, he and his colleague Malik Peiris first isolated a coronavirus from samples of 50 pneumonic patients in Hong Kong and identified this as the infectious agent causing SARS. Their findings and groundbreaking paper on the novel virus would make them famous among academics. Back then, Leo had developed the diagnostic PCR test for SARS, and when he saw the official “red-head” notice from the Wuhan authorities in late December, he began preparing himself mentally to do the same again with the new virus. With a grim sense of foreboding, he pulled genomic sequences of SARS-related viruses from databases and started constructing various primers from consensus regions—genomic regions that had high similarity—to test specificity even before the first genome would be published. He wanted to be ready and have the system up and running for when the genome of the new virus would be released. Speed is critical.

Scarlett might have felt bored about her influenza vaccine work, and she had not been very happy over the years with how little impact and recognition her work entailed. Leo remembered how she always wanted “to be more,” attempted to request first authorship on a paper to which her contribution was not substantial enough to warrant such a demand, and sought to work on projects that were outside the scope of his lab. She pushed him to let her speak at seminars for more exposure or invite guests to the lab by leveraging his name. But science can be very frustrating in that way. Except for some extremely lucky or extraordinary circumstances, scientific work and recognition are slow, gradual, and almost never reach the wider public.

From my perspective and that of people who knew her, it seemed that even after years in a great lab, success did not come fast enough for Scarlett. Like many junior academics hungry for impact, maybe she also desired to be the one to find something that would make her famous.

On January 13th, a bit more than a day after Zhang’s SARS-CoV-2 genome was published online, SARS-veteran Professor Yuen Kwok-Yung gave an interview to a local Hong Kong newspaper that most likely caught Scarlett’s attention. By comparing the genome sequences to published coronaviruses and placing them into a basic phylogenetic family tree like Little Mountain Dog did a few weeks prior, he explained that, while the new virus is genetically distant from the SARS of 2003, the original source might have been bats. He also highlighted that two bat viruses with around 90% similarity, sampled in 2018 in Zhoushan, Zhejiang Province, were the closest relatives of the new virus. The archipelago south of Shanghai in the East China Sea was over 1000 kilometers away from Wuhan. “However, the reason for the similarity of the coronaviruses in the two places is not yet known,” he was quoted as saying. Little did he know that his words would contribute to setting a course of action in motion that would shake the world. Scientific mysteries invite speculation, and Scarlett possibly saw an opportunity to solve that particular mystery of why these geographically distant viruses were so similar.

She looked up the 2018 study he was referencing. It had the apt title, “Genomic characterization and infectivity of a novel SARS-like coronavirus in Chinese bats.” A basic internet search highlighted that the scientists who discovered these bat viruses were affiliated with a military medical university. Jasnah had explained to me how Scarlett was deeply distrustful of the CCP, so it did not take much for her to believe that maybe there was a hidden human connection between the Wuhan outbreak and these bat viruses named ZC45 and ZXC21. After all, why were the two closest viral relatives to the novel virus both discovered by scientists affiliated with the Chinese military? How could a new virus emerge 1,000 kilometers away in a city with one of China’s two high-security BSL-4 labs? Maybe there was a deeper reason why Chinese authorities have not been transparent about the outbreak and lied about human-to-human transmission. It likely seemed to be too much of a coincidence for her, but we can only speculate about the full scope of her motives.

She certainly was not the only one in Hong Kong who distrusted anything and everything coming from China. “Honestly, it doesn’t take much for certain people. Moving outside of the PRC [People’s Republic of China] for any reason and realizing that you have basically been fed a carefully crafted lie your entire life is not exactly a comforting experience,” Jasnah elaborated. She had seen this many times before when Chinese students were moving to Hong Kong. The change in the information environment often leads to a change in their worldview. As for Scarlett, Jasnah told me she had been “a regular watcher” of YouTuber and supposed Chinese dissident Wang Dinggang, who broadcasts under the name of Lu De. For years, he has built a name for himself by attacking the CCP on YouTube. He railed against China’s crackdown on Muslims and pontificated on the US trade war. Scarlett possibly saw an opportunity for recognition, or maybe just a need to share, so she reached out to him and offered her suspicions about the new virus.

It is unclear whether she knew—or even cared about—how much her suspicions would be capitalized on by bad actors at the time. When a group of US-based Chinese influencers suddenly started distributing the first social media posts, videos, and articles in Chinese on January 18th that highlighted these spurious connections to ZC45, ZXC21, and the Chinese military, few consumers within the Chinese-speaking community were aware that the information flooding their news feeds was inauthentic. They had no idea that the information being released was made up for a specific purpose: to manipulate them. “The media outlets that cater to the Chinese diaspora—a jumble of independent websites, YouTube channels, and Twitter accounts with anti-Beijing leanings—have formed a fast-growing echo chamber for misinformation. With few reliable Chinese-language news sources to fact-check them, rumors can quickly harden into a distorted reality,” The New York Times would later report about this ecosystem. Only with some hindsight can we reconstruct where all the activity was coming from at the time.

The ringleader behind these sets of rumors was Ho Wan Kwok (also known as Guo Wengui or Miles Kwok), better known as Miles Guo. He was a reportedly corrupt billionaire and self-proclaimed dissident who fled China in 2014 after sniffing out that he was going to be arrested under allegations of bribery, money laundering, fraud, and rape. Profiting from shady construction deals and political maneuvering for decades, Guo was, at the time, the 73rd richest person in China when his political network was slowly being dismantled by Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. He was losing influence. Before investigators could reach him, he took his money and ran.

Ever since, the exiled tycoon has lived lavishly in the US and found a new political home within the Trump-associated MAGA movement in the US, being a frequent guest at Mar-a-Lago and a close collaborator of then-President Trump’s advisor and Breitbart founder Steve Bannon. In 2018, Guo, with the help of Bannon, entered the media game and trademarked Guo Media, a social media video and broadcasting service owned as a foreign business corporation by a shell company in Delaware. He would later also be the funding source behind Gettr, a Twitter clone and alt-tech social media platform targeting American conservatives that was founded by Jason Miller, a former Donald Trump aide. Miles Guo and Trump’s inner circle had a shared interest in undermining the Chinese government, and Bannon received over a million dollars in consulting fees from Guo, according to investigative reports. With their near-daily video commentary, Guo and Bannon’s opinion pieces would flood GNews, and they accumulated a decent following, especially among the Chinese-speaking diaspora, who saw Guo as some kind of anti-CCP warrior and hero, a false image he crafted for himself.

The billionaire has also cultivated a set of popular influencers and dissidents to boost his profile, including John Pan, who was among Mr. Guo's inner circle until December 2019. A dissident, Mr. Pan would later explain to ABC News Australia how he became trapped in Guo’s anti-CCP activism and how he and the initial 18 members of the inner circle discussed how to orchestrate viral media campaigns against the CCP. "We're talking about how we would promote the information that Guo was leaking out, how we spread that information to the world. No matter [if it was] true or false," Mr. Pan was quoted as saying by the news organization. He explained, as an example, how Guo once encouraged his key followers during the 2019 Hong Kong democracy protests to spread a rumor that martial law was imminent in the territory. People predisposed to this kind of messaging in times of crisis ate it up uncritically, and Guo’s followership and influence grew, especially in Hong Kong, where there was a massive hunger for CCP-independent information in Chinese, and he was pumping out propaganda content daily.

When the outbreak in Wuhan emerged in early 2020, it presented a tremendous opportunity for Guo’s operation. On January 18th, Miles Guo created the marching orders and, in a live stream, passed them to his followers. Together with Lu De, his “chief propagandist,” he used Scarlett’s suspicions and persona to concoct a bioweapon myth based on the spurious connections to the 2018 bat viruses. Some of Guo’s sock puppet accounts (fictitious social media accounts controlled by somebody else) are still visible today. They would all blast out the same copy-pasted message:

武汉的类SARS冠状病毒就是来源于中共军方2018年从舟山蝙蝠身上发现并分离的新型冠状病毒。如图改病毒序列可以在美国国立卫生研究院的基因数据库找到(NIH的GenBank),由南京军区军事医学科学研究所递交。并且通过技术故意更改舟山蝙蝠病毒,适于人类传播的新病毒.

Translation: The SARS-like coronavirus in Wuhan originated from a new type of coronavirus discovered and isolated from bats in Zhoushan by the Chinese military in 2018. The virus sequence shown in the picture can be found in the gene database of the National Institutes of Health (NIH's GenBank), and submitted by the Institute of Military Medical Sciences of the Nanjing Military Region. And the Zhoushan bat virus was intentionally changed through technology, a new virus suitable for human transmission.

These identical messages contained the same images: one was a screenshot of the GenBank (the US National Institute of Health’s sequence repository) website showing the 2018 bat virus entries, and the second was of the 2018 publication with the military hospital affiliation of the last author highlighted separately. Disinformation often uses real but decontextualized information as the supposed “source” for its false or manipulative claims. There was no question that all of these identical posts came from the same originator. It was low-effort but effective. Dozens, if not hundreds, of sock puppet accounts and bots would amplify this message on Twitter, Facebook, WeChat, Weibo, and other social media platforms. Lu De and other influencers in Guo’s network would do the same. The groundwork had been laid, and audiences were primed.

On January 19th, the influencer Lu De would put on a suit and get ready for his show. In his 80-minute episode devoted to an “unnamed whistle-blower” (later revealed to be Scarlett), Lu De boasted that he had heard from “the world’s absolute top coronavirus expert” some troubling news that China was not being transparent. The Chinese military had actually created the virus. “I think this is very believable and very scary,” he said. Broadcast on GNews, Vimeo, and YouTube and then amplified by his tens of thousands of followers, his show hit like a bomb, with hundreds of thousands of clicks and engagements. The other influencers in Guo’s network followed suit, with the inner group alone reaching around 143 million views in the following weeks, according to an investigation by the Digital Forensics Research Lab, an organization that tracks disinformation.

Yet this first media blitz would only be the beginning of their success story. Guo’s biggest move was still a few months out. Scarlett was to assume a much bigger and way more controversial role, maybe the one she always wanted. Leo Poon warned me that he might not want to answer any more questions about her because “I am sure she will use all my comments on her to promote herself and to discredit science. I personally do not want to give her any chance to make up new stories. Of this reason [sic], I might refuse to answer questions about her.” Jasnah was equally dismayed. “I swear, if that whole fucking thing comes back to Miles fucking Guo, I don’t know what I would do,” was her response when I laid out how I viewed this particular origin of the bioweapon myth. We humans like to believe that if circumstances had just been a bit more favorable, maybe events could have played out quite differently. Unfortunately, the reality was not that simple.

I have been sifting through early reporting to investigate where the different “man-made” conspiracy theories originated. Reconstruction is a tedious task, eating away hours after hours; sitting many late nights chasing down outdated links and articles and deleted social media posts in the internet archive with tools like the Wayback Machine. However, when taken together with first-hand accounts from people on the ground who lived through it, a fuller picture emerges. Rumors, myths, and controversy after outbreaks are common, maybe even unavoidable. Every single outbreak, from the plague to the various influenza pandemics to “SARS, MERS, EBOLA, ZIKA, you name it,” Leo Poon would finish my exact thoughts. Each one of them was followed by conspiracy theories that blamed humans for it, and a substantial number of people were willing to believe any explanation given, no matter how absurd. The best I can tell is that we humans have a tendency to seek and see agency behind grand catastrophes. We also tend to assign blame to an outgroup when things go wrong.

The bat viruses collected in 2018 in Zhoushan might have been the earliest of the man-made conspiracy theories that received inauthentic amplification and went viral, but Miles Guo and his gang of influencers were, of course, not the only ones who tapped into the political moment. General anxiety and uncertainty at the beginning of any crisis lend themselves to media manipulation. In fact, multiple related origin myths would emerge separately and almost simultaneously all over the world, sometimes mingling and converging topically but gradually and independently gaining more attention.

For example, on January 20th, Russian disinformation operations in state media started to pick up on the man-made theme, albeit with a twist: they platformed self-proclaimed biosecurity expert Igor Nikulin, a political activist with no discernable expertise, who argued that the US created the virus and used it to attack China. He first expressed this belief on Zvezda, a state media outlet tied to the Russian military, and repeated it dozens of times in other interviews with mainstream outlets that seemed to eat it up uncritically. This facade of laundering information through supposed independent voices and intermediaries is neither new nor unexpected from Russia. The KGB had run a similar disinformation campaign in the 1980s, today known as “Операция Инфекция,” a.k.a. Operation Infection (originally Operation Denver), to blame the emergent AIDS pandemic on their foreign adversary, the US. Iran and China would follow this playbook in due time.

In the US, on January 21st, a QAnon influencer expressing strong anti-vaccine sentiments named Jordan Sather picked up and amplified to his hundreds of thousands of followers a different conspiracy myth, creating roots for a set of ideas that would later resurface occasionally under the name “Plandemic.” He alleged that the pandemic was man-made for nefarious purposes, such as selling vaccines for profit. His evidence? Links to an old patent entry. He claimed researchers had produced a vaccine against the new virus, but now the patent was about to expire. That patent he linked to does, in fact, exist. It was work that was partially supported by grants from the Bill Gates Foundation and pharmaceutical companies. What a coincidence, he echoed on social media. “Was the release of this disease planned? Is the media being used to incite fear around it? Is the Cabal desperate for money, so they're tapping their Big Pharma reserves? Are there vaccines already being manufactured to "fight" this?” Sather did not realize or care that the patent in question was for a vaccine against SARS that broke out in 2003, not SARS-CoV-2. But of course, he did not need to get the facts right; his posts prompted countless online engagements all the same, spreading the patent myth far and wide.

A few days later on January 23, with a veneer of serious reporting, the UK tabloid Daily Mail amplified another very influential myth that would also spread like wildfire. A Western scientist wrote in a 2017 Nature News article a warning about how the Chinese culture of hiding problems and lack of transparency might pose an issue for working in BSL-4 labs like in Wuhan. The Daily Mail’s insinuation was clear: The new virus might have leaked from this lab in Wuhan because of bad biosafety. The article bolstered its claims with the commentary of a bioweapon fearmonger who had an axe to grind with virological biosafety for years. It gave a veneer of serious reporting. However, BSL-4 labs only work with known, very dangerous pathogens, not random bat viruses whose pathogenicity has not been characterized yet. Ordinary bat viruses cannot infect humans, so they could be studied under BSL-2 at the time. But the high-security BSL-4 sounded more dangerous, so it was good for headlines. That any such proposed lab accident from a BSL-4 lab would have, by necessity, required knowledge and documentation of this hitherto unseen virus first, or that no unknown virus ever leaked from a high biosafety lab to the best of our knowledge, was conveniently withheld from readers.

On January 23, 2020, Wuhan, a megacity of 11 million, went into lockdown. Outbound public transport was suspended. Public activities were canceled. Flights got grounded. Panic set in. The news sent shockwaves around the world. The outbreak in Wuhan had been a narrow issue for most of the world until this point. Suddenly, it really captured the attention and imagination of the masses. The infosphere exploded into overdrive. With a large global audience came a huge market demand for more outbreak information and answers, a need that scientists and institutions could not satisfy immediately. However, commentators, bloggers, and influencers were all too happy to fill those gaps with more rumors, speculations, and falsehoods, often by scraping together bits and pieces from dubious internet sources and Google searches. Speed over accuracy is how you make gains in the attention economy. It was like putting gasoline on a fire. With the media attention surrounding the dramatic lockdown announcements, conspiracy theories exploded into the mainstream. The early conspiracy theories received the biggest amplification from crowd-sourced interest. It’s called first-mover advantage. Everybody was sharing, retweeting, and commenting on content that featured the Wuhan outbreak and the mysterious virus as its topic.

On January 25, Guo Media’s GNews announced in an article that the CCP admitted to the bioweapon release—a complete fabrication—by providing a Word document full of “evidence” for the bioweapon. That document included screenshots Guo and his network had spread before, along with some loose commentary and descriptions to create the superficial appearance of merit. It was happily picked up by fringe and right-wing media as well as partisans.

On January 26, the obscure Indian blogger Great Game India amplified social media chatter by publishing an article titled Coronavirus Bioweapon – How China Stole Coronavirus from Canada and Weaponized It. The piece was a complete fabrication, distorting a legitimate July 2019 report from Canada. Around the same time, the U.S. partisan tabloid The Washington Times picked up similar rumors, blending Daily Mail reporting from three days earlier about biosafety concerns with baseless speculations from a questionable Israeli intelligence analyst. This analyst reiterated the false Canadian spy story and claimed the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) was involved in bioweapons research. The narrative, fueled by the Israeli bioweapon analyst’s claim, quickly gained traction within right-wing media circles.

On January 29, the blogging outlet Zerohedge started doxxing a Chinese scientist, accusing him of being responsible for the pandemic. The outrage that followed the blaming of an individual was good for amplification; major media outlets would cover these lies in an attempt to debunk them, but this only added to their spread. The poor scientist’s name, photograph, telephone number, and email address were shared over 11,500 times on Twitter. Zerohedge would later be temporarily banned on Twitter for doxxing because it violated company policies. But this was only after the blogger pulled off his biggest stunt two days later.

On January 30, Indian researchers published a preprint finding an “uncanny similarity of unique inserts” in the spike protein, identical to peptide fragments found in HIV. The uncanny sequences were just arising out of coincidence, and the preprint would be withdrawn later, but not before amplifiers on social media picked up on it and ran their mouths off. In parallel, foreign policy hawks like Francis Boyle and US senators like Tom Cotton were publicly entertaining the idea that the new virus was a bioweapon or could have come from the Wuhan BSL-4 lab.

On January 31, ZeroHedge dramatically amplified the bioweapon myth by creating a fairytale based on merging many circulating themes. A chimera bioweapon myth, if you will. Integrating the Daily Mail reporting about biosafety warnings, the pick-up of Great Game India’s Canadian spies, the fresh preprint about supposed HIV sequences found, and the scientists he felt justified doxxing two days earlier, the blogger built an engaging storyline for his audience that included many of the prevailing themes and sentiments. The emotional truth of the narrative went along the lines of “Chinese scientists have ulterior motives; they wanted to create a bioweapon, but WIV was lacking biosafety, and it escaped.” True or not, it was a sentiment so powerful that it would never leave the conversation again in US right-wing ideological circles, and often beyond.

These were, of course, only a fraction of the early narratives bubbling up in various corners around the world. Nobody can accurately trace them all, figure out where exactly they all came from, or identify who was “patient zero” for their spread. The only thing that we can say for sure is that after the dramatic lockdown announcement in Wuhan brought global attention, a week of wild speculations, viral conspiracy theories, and crowd-sourced myth-making followed. Everybody wanted to talk about it and be seen talking about it. Within that week, the dynamics of our global interconnected information systems made sure that the unsubstantiated idea of a man-made virus would be broadcast all around the world. China might have wanted to control rumors and craft its heroic response narrative, but its mantle of silence did not extinguish the fire; it fueled the flames.

Aristotle famously claimed that nature abhors a vacuum. After spending way too much time on social media over the last few years, I became pretty convinced that, just as nature fears a void, the internet fears an information vacuum. Whether fiction or fact, truth or trickery, myth, magical thinking, or outright manipulation, whatever is offered seems to be more desirable to us than having to wait for information. This is human. Especially in times of ambiguity and dire peril, we tend to prioritize information speed over accuracy.

Consequences be damned.

Excerpted from Lab Leak Fever: The COVID-19 Origin Theory that Sabotaged Science and Society by Philipp Markolin.

Copyright © 2025 by Philipp Markolin. All rights reserved.

If you are interested in the origin of the pandemic, and the manipulation campaigns around it, you can find more information about the book here: www.lab-leak-fever.com

Release day in Germany/Austria/Switzerland: 20. April 2025

Release day Global: TBD*

*Due to geopolitical sensitivities, this book is currently unavailable outside of Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. My US publisher deemed the risks to severe to go forward with the book after the US elections, and I can not blame them. But that means that US/UK readers and elsewhere will have to be patient, while I am looking for support and solutions to make this story available to everybody eventually.

Free Access to read-only version:

While I can not gift away the books for free because of printing and other costs; I believe this topic is too important to be kept behind a paywall.

Anybody who wants to read how the pandemic began deserves access to good information; so if you can not afford to buy the book or ebook, please reach out to me with a quick explanation and I will provide access to a digital reader-only version* for free that can not be downloaded and copied, no questions asked.

Just go to www.lab-leak-fever.com and write in the form below “Digital reader-only version” and a sentence or two about your circumstances (for example: “Hi, I am a student in Austria/Mexico/Thailand, can’t afford to buy but really want to read it”) and I will grant access to the book to you via your email address.

This is a great read, and you’ve written a page turner for anyone following COVID origins, and the cast of characters who emerged in its wake. I also appreciate your original reporting, getting interviews with two of the top Chinese scientists, George Gao and Shi Zhengli, and letting us see a glimpse into their thinking.

One suggested edit, unless you are read into the highest levels at every lab in the world, your writing, “no unknown virus ever leaked from a high biosafety lab” is likely not a sentence you can back up. Nor can you definitely write, as you do, that no BSL-4 worked with “random” bat viruses vs. “known.”

Those details are, as they say, known unknowns.

Even in the US, as Alison Young’s investigative reporting for Pandora’s Gamble shows, it’s not public what was in the untreated biolab wastewater that went spilling out of the USAMRIID biolab tanks in 2018 and onto the lab’s grounds, likely into Frederick, Maryland’s waterways.

CDC shut that lab down because of if its safety problems, details of which are still secret. Someone knows, but they haven’t shared what viruses, if any, were in USAMRIID’s BSL-3 & BSL-4 leaking biolab water, so, again, saying a virus has “never” leaked, as you do, currently is not even verifiable for US labs.

In addition, it’s known that labs worked on unpublished bat viruses, bat virus chimeras, or their parts, before COVID. RML has a BSL-4, they had live bats and did unpublished coronavirus work. Has RML given you details about their BSL-4 work and the sequences and RBD’s they worked on? NIH went to court to fight releasing their RML coronavirus secrets and thus even the coronavirus work at this NIH intramural, DOD-funded, US lab are not fully or publicly known.

Your paragraph for suggested edits is below. Hope you find someone to publish the entire book in English, as it would contribute to the debate and discussion.

Secrets are still out there, as is the original host species, it’s said.

Congrats on your book.

“However, BSL-4 labs only work with known, very dangerous pathogens, not random bat viruses whose pathogenicity has not been characterized yet. Ordinary bat viruses cannot infect humans, so they could be studied under BSL-2 at the time. But the high-security BSL-4 sounded more dangerous, so it was good for headlines. That any such proposed lab accident from a BSL-4 lab would have, by necessity, required knowledge and documentation of this hitherto unseen virus first, or that no unknown virus ever leaked from a high biosafety lab, was conveniently withheld from readers.”