Background:

In many ways, a controversy around the origins of SARS-CoV-2 was unavoidable. Humans have blamed unexpected or novel diseases on others for a long time, and the uncertainty and impact of pandemics specifically lend themselves to speculation, fear, and suspicion. Every major pandemic, no matter if 1918 influenza, AIDS, SARS-1, H1N1 influenza, or Zika virus had caused substantial parts of the population to believe it was somehow ‘man-made’, and SARS-CoV-2 is no exception.

But something else is quite different this time around.

With every new report from scientific experts putting the origins of SARS-CoV-2 on zoonotic spillover (likely via wildlife trade), an online counter-narrative about a ‘lab leak’ origin is bound flare up again.

A counter-narrative that is increasingly decoupled from facts and science, but nevertheless producing a flurry of activity and content drowning out expert opinions, creating uncertainty and filling it with alternative theories. A symptom of a deeper problem in our information age.

An emerging consensus

Scientific uncertainty around newly emerged pathogens is common, but not everlasting. A laboratory accident hypothesis (‘lableak’) was a justified scientific consideration for the origin of SARS-CoV-2 when it first emerged. Before details on the new pneumonia were known, Shi Zhengli, the head of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, famously had pondered whether it might have been a coronavirus from her lab when on a trainride back from a conference. She would not be the last to check. Scientists all around the world considered it a plausible route of emergence, given that coronavirus work was performed in the city where the virus first emerged.

Alas, as it would turn out, SARS-CoV-2 was a novel virus nobody had ever seen before, neither inside nor outside of labs. After almost three years of intensive research, a detailed body of scientific evidence created by hundreds of independent scientists provides the basis for a scientific consensus around a ‘natural’ origin scenario for SARS-CoV-2. Here is the bite-size version:

It is not perfect knowledge (that is anyway not how these outbreak investigations work), but still entirely sufficient evidence to rule out all plausible lableak hypotheses (check references for further support). Spillovers rarely divulge all their specifics and mysteries.

In contrast, the lab leak narrative has been polstered by an ever-changing amalgamation of mutually contradictory conspiracy myths, that moved the goalpost, morphed talking points and manipulated public perception over the years.

And yet, public conversation is not reflective of this reality by a long shot. Even more frustratingly for scientists, no amount of evidence they could hope to produce will be able to change minds given our currently broken info sphere.

Scientists only know to fight fictions with facts, but that is insufficient for truth to prevail in the information age

Despite detailed evidence and a scientific consensus ready at hand, more access to good information, experts and the knowledge of history, even with a credible and illuminating warning shot in the form of SARS-1, surveys in the US show that a majority of citizens have trouble wrapping their heads around the scientifically uncontroversial zoonotic origin of the Covid-19 pandemic. Many even have a feeling that something untoward has happened and that ‘ordinary’ people will be kept in the dark about it.

This is no coincidence, but the result of asymmetric forces, self-serving actors and another viral pathogen that has spread around the world and infected something even more vulnerable than our bodies; our minds.

An infodemic of crowd-sourced distortions

The disruption of our shared information spheres through technology, from internet freedom all the way to search engines, social media and microtargeting algorithms, has fundamentally reshaped how we encounter, consume and use information. Information has a special function in society, it does not only inform out choices, it also shapes our perception of reality. Many of the frictions in today’s connected societies boil down to the fragmentation of our perception of reality through varied access, exposure and consumption of information, one of the main drivers of our current epistemic crisis.

Epistemic crisis: When large parts of society lose the ability to assess what is real or true

From vaccine safety to Ivermectin, mask efficacy to whether Covid-19 is just the flu, the pandemic has seen it’s fair share of misinformation. The prevalence and success of many conspiracy myths, including the false belief in a ‘lableak’ cover-up conspiracy, are in this sense just part of the bigger picture. There are many social, psychological, technological and political factors that contribute to our current epistemic crisis. What is less clear is why some of these conspiracy myths born out of uncertainty persist after scientific evidence brings clarity on an issue. In other words:

Why do baseless conspiracy myths hardly ever go away on social media?

I think this is a question worth exploring a bit deeper.

First, we have to understand that social media is not an even playing field when it comes to information, it is not a space where the “best’’ (most truthful, accurate, contextual, relevant etc…) information wins out. Quite the opposite, facts are often boring, scientific reasoning is nuanced and often complicated. Conspiracy myths are accessible, engaging, emotional and often outrageous. They catch eye-balls and hardly ever give them back. They have an asymmetric advantage in the fight for our attention on social media.

But this is just the tip of the iceberg. There are many asymmetric forces on social media that systematically shape our shared information sphere in their image, and to all our detriment.

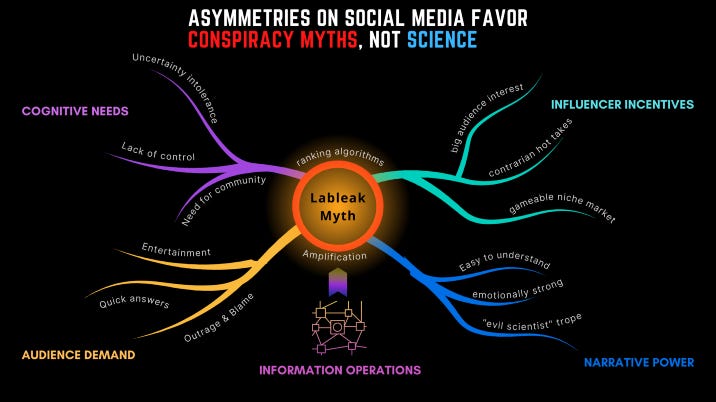

The lableak myth is so successful because it can make use of the many interrelated asymmetries of our broken information sphere.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity…— Charles Dickens, Tale of Two Cities

An illustrative way to understand some of these forces is to consider information as a product, and influencers as information merchants.

Any topic that garners a lot of attention is a potential source of income for influencers. The more eyeballs something attracts (or can be made to attract), the more money can be made from it, directly or indirectly.

The easiest way to game the attention system is to create any information product that is just very addictive, broadly appealing, or easily shareable. For example endless cat videos, but also click-bait and nasty political memes.

However, click-bait or cat videos have huge market competition, there is zero creator loyalty and consistent monetization with these information products is almost impossible.

So a more successful business model for influencers is to create an addictive information product that has a unique appeal, or that is custom-made for a specific audience of the attention market. In marketing, we call the former ‘USP’, a unique selling proposition, and the latter targeting a ‘niche market’. This is where gurus, contrarians, political commentators, culture war spin doctors, and of course information grifters come in. For ease, I will keep using the general term ‘influencers’.

Influencers are experts in sensing what a niche audience wants to hear, developing parasocial relationships with their targeted group, and doing everything in their power to create outrageous, polarizing, or addictive content for their audience ‘tribe’.

The content of the information product does not have to be bound by accuracy, reliability, context, facts or any other metric we ‘consumers’ would usually care about in information. Sticking just to “truthful content” might even be a disadvantage when optimizing for engagement and trying to grow an audience.

What truly matters on social media is that the information product can be “sold” to (read: capture attention of) as many people as possible, and this is what influencers really care about. This is basically why intuitive, emotionally engaging, or populist narratives and ideas eat everything else on social media.

As I have written elsewhere, these dynamics are of course incentivized and empowered by content ranking algorithms, our own confirmation-seeking and other psychological biases, as well as echo chambers and other attention economy “winner-takes-all” mechanisms.

Conspiracy myths thrive in such an environment.

To give you a bit of an intuition, I just want to highlight two asymmetries arising from the crowd-sourced distortions of our info sphere and map how they interfere with the natural vs. ‘man-made’ origin discussion.

A) The asymmetry of narrative power

We humans are story-telling species. Stories is how we make sense of our world, we crave heroes and villains, the fight of good versus bad, we seek stories that we can relate to, that are easy and intuitive to understand, that engage us emotionally, entertain us, or make us feel good about ourselves.

Influencers are interested in creating and selling good stories for their bottom line, and this helps conspiracy myths more than science. After all, fictions can be optimized for audience engagement, facts can not.

The ‘lableak’ idea has many psychological, cultural and social advantages that make it a more powerful narrative than a zoonotic origin. First, it is very intuitive to understand; somebody fucked up. It plays into our cultural practice of blaming diseases on people outside our tribe, instead of our own failings and responsibilities. It plays into our tendencies to view world events as product of conspiracies rather than bad luck or randomness. Lastly, it offers us power. If only we can stop this minority of (in this case) “evil scientists”, we could prevent a pandemic from happening ever again. Pandemics have been with humanity for millennia, blaming them on others it is literally a story old as time for tribal beings such as us.

Compare this to the ‘zoonotic’ idea, where there are no concrete actors, but our collective ravaging of nature, farming practices, economic incentives and global transport hubs that are all somehow responsible for spillover risk. What about the distribution of bats all over South East Asia, the incredible diversity of hitherto unknown viruses in the wild, and how does zoonotic transmission even work? How can we understand all the interconnected layers to this problem? These issues are way harder to intuitively tackle, in fact, they leave the feeling that we might not be able to prevent the next pandemic, that we are somehow guilty but not in control. That we will see more and more horrible pandemics, and nobody knows what actions we even gotta take to stop it. Not the sexiest narrative to say the least.

Guess which story finds itself more likely shared and engaged with, and which narrative has more influencers willing to create content for it on social media?

B) The asymmetry of audience demand

Going by the motto of ‘the customer is always right’, many influencers create content that the audience wants to see. This is a very straightforward business model and it might help sales of information products enormously, given our own propensity to seek confirmatory information and other psychological biases.

Catering to ever-changing audience demand is one of the biggest challenges for influencers, because attention is a fickle thing. Once an audience has been cultivated by an influencer, they need to keep selling information products to keep their market share of their niche. So what many end up doing is creating what I call ‘meme content’, information products that are designed to convert people to the idea without offering any true argument or value.

There are of course several strategies for influencers to sell meme content, for example being confident or entertaining delivery of information, or by fulfilling a figurehead role based on their identity (“Black influencer saying actually ‘whites’ are discriminated”, or “Former employee calls Ecohealth alliance organization a CIA Front“…), or by creating contrarian counter-narratives to differentiate themselves from genuine expert opinion (“scientists don’t tell you how climate change is actually good for us”, or “SARS-CoV-2 was a failed vaccine experiment”…), or just bringing their unrelated and absurd pet talking points to any new topic. (“Russia is gonna win the war because they are not woke”, “BSL-2 biosafety is like working at a dentist office”).

The point is: Conspiracy myths are cash cows. They allow influencers to sell junk information products at high volumes based purely on grift, identity, manipulation, fantasy or intellectual virtue signaling, instead of real informational merit that comes from research and acquiring topical expertise.

Speaking of which, domain experts in contrast often communicate science by relativizing every statement with caveats, and by expressing uncertainty and limits of their knowledge, using a vocabulary that is hard to digest and alien to non-experts. No matter the informational merit hidden in the content, no larger audience can or wants to spend the necessary time or energy to engage with these information products.

And that has unforeseen consequences.

Asymmetries pose a bandwidth problem for society

Information is a special product because it shapes our perception of reality, we need reliable information to act and make sense of our world, yet our attention is a limited resource. On social media (and more and more in wider media as well) the overt favoritism of simplified, emotionally engaging narratives and personalized niche content delivered by contrarian shysters, marketeering influencers, or other engagement gurus destroys any navigable level of signal-to-noise ratio on any topic for the wider public.

The result of these asymmetries is first and foremost one thing: Unbearable noise.

But noise is not without consequences. If we cannot browse reliable information, if we lack domain expertise, time, or energy to deeply engage with the topic, we have to rely on our trust in others to reach actionable certainty on any topic to navigate modern life.

However, relying solely on trust, not expert institutions, scientific consensus, or factual reporting to inform one’s opinions is dangerous in a world of fragmented realities. Fake experts, political commentators, and other attention stealers have a far wider reach than actual trustworthy sources, and usually stronger personal appeal or skill to manipulate us into trusting them. (I’d even say: never trust an influencer, always look for what the boring ‘public institutions’ have to say)

Even worse, in an ideologically polarized environment, the system-imposed need to outsource our opinion formation on any topic to our trust networks will often result in our dependence on unreliable proxies already in our ideological network, or demand of citizens to choose the most stomach-able lowest common denominator tribe ideology they can live with to get their information from.

And this brings us to the foreseeable future of the lableak conspiracy myth: Weaponization by political actors.

The conspiracy myth playbook

The best predictor of believing in a conspiracy theory? Already believing in others

Has anybody noticed something weird going on in the US?

January 6th and Trump’s election steal myth, anti-vaccine conspiracy fantasies, lableak and biosafety fearmongering, QAnon, white genocide, moral panics about immigrant caravans or LGBTQ minorities; many of the most hateful and conspiratorial narratives seem to aggregate around a political movement, leader, and ideology. Prima facie, it is odd to see such a diverse set of conspiratorial ideas neatly align with a large segment of the population that happens to vote for the same political party under the whip of an autocratic leader. Even before the weird cult-like and parasocial worshiping of its demagogue, the MAGA movement is primarily animated by conspiracy myths, and this is dangerous.

It is also a strategy.

Political leaders and movements can use conspiracy myths to gain power, and this is not unique to the US by any means, we could also talk about Poland, Italy, and Hungary, or Myanmar, Nigeria, the Philippines or Brazil, and many other nations currently in democratic decline. Making use of conspiracy myths is one of the oldest tricks in the book that authoritarian leaders and movements use to attack opponents, galvanize followers, shift blame or responsibility, and undermine institutions that threaten their power.

There are of course many cognitive, psychological, behavioral and social antecedents that drive a conspiratorial mentality, which I can not go into here. I just want to highlight one striking characteristic of being prone to conspiratorial ideation:

It does not stop with any specific conspiracy

The best predictor for believing in a specific conspiracy theory is already believing in other unrelated conspiracy myths.

That is a simple enough pattern to figure out for example by the ranking algorithms that nudge, lure or drive people down rabbit holes of ever more extreme conspiracy narratives about any topic. This is also a simple enough pattern to use for political targeting.

Conspiracy myths can be used for political targeting

In many places around the world, we are currently observing targeted online mass mobilization around shared conspiratorial narratives, either shaping available conspiracy theories towards political ends or manufacturing new conspiracies that tap into conspiratorial audiences for a strategic purpose.

Most politicians who share conspiracy myths are usually regarded as less trustworthy, but certain political actors can create the authentic impression of an ‘outsider’ capable of changing the system. Some experiments suggest that lying demagogues appeal ‘authentic’ to people who perceive the current system as unjust or illegitimate.

In that sense, conspiracy myths in themselves might present another asymmetry of the information age: in what type of political actors (spoiler: it’s never the friendly, normal ones) can make full use of them to further their strategic aims. Demagogues have a clear incentive and an advantage when they can weaponize available grievance, hate or fear narratives for personal gain, but their political opponents can not.

So if you see the Trump White House putting up this garbage, it needs to be treated as the fascist propaganda that it is: They are weaponizing an emotional myth for personal and political gain.

The implications of this could fill many books, but in short: This is bad for science, for pandemic prevention, ultimately for the public good, our democracy and the planet.

If we still care about any of these things.

Conclusion

More hopeful times would see the scientific process of slowly approximating more likely truths with shared pride in our human ingenuity.

Unfortunately, we live in times of epistemic crisis, inhabiting fragmented realities of our own making, segregated from each other along arbitrary lines enforced by algorithmic systems and social mechanisms we have yet to wrap our head around. A broken info sphere creates new vulnerabilities for a democratic society, and new informational pathogens have used the opportunity to infect the minds of unwitting citizens.

The real reason why the lableak conspiracy myth will not die despite ever-mounting scientific evidence against it is because myths hold a lot of asymmetric power in the information age.

Conspiracy myths have the power to hold us scared and needy audiences in front of our screens, the power to enrich influencers who propagate them, and the persuasive power malicious actors crave for their ascent

In contrast, science brings only one asymmetric power: The power to free ourselves of false beliefs, no matter how popular.

Especially in the information age, I believe true agency over our lives can only come from perceiving reality as it is, not from living in false myths others have created for our shallow convenience and their benefit.

But that is up to personal preference, I guess.

References

Klofstad CA. et al., Humanities & Social Science Communication, 2019

Jiang & Wang, Science, 2022 (Perspective)

Worobey M. et al., Science, 2022

Pekar J. et al., Science, 2022

Stein RA. et al., Int J Clin Pract., 2021

Ren ZB et al., Curr. Opin. Psychol., 2022

Hahl O. et al., American Sociological Review, 2018

Green R. et al., Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2022

Goreis A. & Voracek M, Front. Psychol., 2019

Further reading and resources:

Blog: The case for a zoonotic origin of SARS-CoV-2

Blog: Lableak myth influencers & their fear-based communication tactics

Blog: How algorithmic curation empowers controversies

Video: Long-form discussion with SAGO member Dr. Carlos Morel (SAGO is the WHO’s scientific advisory group on the origins of pandemics)

Video: Long-form discussion with bat ecologist Dr. Alice C. Hughes and the risk of SARS-CoV-3

Video: Long-form discussion about lab leak uncertainties with virologist Dr. Stuart Neil

I will be writing more about asymmetric power in the information age. If you are interested in featuring my upcoming articles, or working with me on a related project, please reach out.

This article took time and effort to conceptualize, research, and produce, but I do not want it locked behind any type of paywall.

I see this work as a public good that I send out into the void of the internet in hopes others will get inspired to act.

So feel free to use, share or build on top of this work, I just ask you to properly attribute (Creative Commons CC-BY-NC 4.0).

If you feel this work should have some compensation, or want to give democratic forces a boost, please consider donating in support of the Ukrainian people, who do their utmost to defend themselves and democracy in wider Europe from the terrorist assault of Putin’s Russia.

Decades of asymmetric misinformation warfare and conspiracy myths have contributed to gradually shaping the Russian nation and people of 150 million to become cynical, disengaged, or ignorant enough to allow a kleptocratic madman in power to usher in a new dark age of imperialist war, slaughter, and nuclear escalation. While absolutely terrifying, this is merely one outcome of a broken info sphere & epistemic nihilism on a population scale. Let’s not find out all the others.

When nothing is true, everything becomes possible

But the buck has to stop here. With us.

Dear Phillip,

Of ALL my remarkable discoveries on Twitter, today, Thanksgiving 2022, I found YOU and this most profound writing. It is what my mind has been screaming for 7 years or more. The Covid-19 pandemic and the rise of the authoritarian movement (..and the astounding related demographics and related social media influencers) became a searing example of the inability to define “truth”, to the detriment of humanity. I watch with fear and horror as things have played out.

Your writing has restored my sanity. I will share it as widely as possible and I would love to help with projects if my skills are of use. DM me for contact information. Patricia Berrini