Shadows of the coming Dark Age for science in the US

Some analysis of the recent successful attacks on science and scientists; and a warning for democratic citizens

Background:

Yesterday, the Washington Post reported that the Stanford Internet Observatory, housing brilliant researchers studying disinformation, collapsed under pressure. A few weeks ago, a critical non-profit for pandemic prevention was suspended after a smear campaign culminated in a show trial, the second victim in the last year after the quiet cancellation of USAID’s DEEP-VZN program. Virologists have been dragged in front of Congress in absurd witch hunts for months now, and that continues. Last week, an outspoken vaccine scientist was openly intimidated by politicians abusing the power of the state. In mainstream media, the New York Times pushes the false lab leak myth again with three separate pieces in the last few weeks; largely in service of legitimizing political attacks on Dr. Anthony Fauci and pandering to rightwing audiences. And the NIH will likely be split, restructured, and brought to heel next if Republican House members get their will. Oh, and a right-wing billionaire has bought and weaponized a whole information ecosystem against scientists for personal pleasure.

These events are not only related to each other, they are a manifestation of a larger trend that started years ago, but dramatically accelerated this year because of the 2024 presidential election. It features a particular cast of actors, audiences, and ideologies aiming to consolidate their power over society. Their recent successes are bad news for democracy in the United States.

Why is this happening?

Let’s take a closer look.

The information age changed power dynamics

The attention economy inadvertently changed how information is used in society. We build our institutions and democratic society based on two assumptions:

First, that information should flow freely between citizens.

Second, citizens deserve and value good information, meaning content that is factual, timely, relevant, contextual, and truthful.

However, the emergence of broadband internet, smartphones, and social media has fundamentally challenged these assumptions. Maybe they were naive in the first place. Today, the gradual commodification of our attention has transformed the role of information in society into a new type of digital product that we exchange for entertainment, services, profit, or power.

The informative merits of those new digital products, the accuracy or truthfulness of their content, became secondary.

A viral “get rich” cat meme is more lucrative than an educational essay about poverty alleviation.

A misleading video clip smearing a political opponent is more persuasive than an analysis of a policy plan.

A false myth feels more emotionally satisfying than a dry scientific study.

There are few regulations and no enforcement on what can be said or shared online to gain attention and to make one’s digital product stand out. Spreading falsehoods comes with no detrimental consequences but often large benefits. It is fair to say that most content we get to see in our feeds has become a means to an end rather than a reflection of shared reality. Most content on various social media platforms, mainstream news outlets, and the internet blogosphere today is optimized to further the financial, social, or political goals of information merchants, media manipulators, or just our needy selves.

Platforms, algorithms, and crowds asymmetrically favor content that has a unique appeal, catches eyeballs, and is ideally custom-made for a targeted audience of the attention market. Information has to spread or it is dead. These new rules apply to everybody; public institutions, established newspapers, legacy journalists as well as an emerging class of influencers, cranks, snake oil salesmen, conflict entrepreneurs, political commentators, shadowy marketing businesses, and foreign actors alike.

Because of these systemic pressures, old and new information merchants have come around to see their core mission or business not in creating informative content, but in hacking the velocity – how well their content spreads through social networks – of the digital products they rely on. The goal of content creators (no matter if marketers, writers, influencers, podcasters, pundits, or politicians) is to make their digital assets, product ads, opinions, ideology, or activism go viral, reach a specific target audience, steal their attention, and get them emotionally engaged or invested in whatever they are selling.

The problem for society arises from the fact that information is a uniquely influential product. It colors our perceptions of reality and guides our understanding of ourselves and the world we share with others, often unwittingly. No human lives in a vacuum, our thoughts, feelings, and beliefs tend to not fully be our own. They are shaped by our social environment and by circulating information that manages to grab our attention and engagement. All too often, in our modern information environment, whatever goes viral or reaches the top of the news cycle not only influences what we talk and think about for the day (i.e our public discourse), but also gradually constructs our identity and worldview over a long time.

In other words, shaping the discourse bestows a certain power over society. “If you make it trend, you make it true” Renee DiResta from the Stanford Internet Observatory puts this phenomenon more aptly. That is why, in the information age, too many politicians, influencers, interest groups, cults, businesses, and covert state actors have become information combatants; an army of velocity hackers, internet activists, and media manipulators aiming to shape the public discourse in their favor. Renee summarizes their aims as gaining “popularity, persuasion, profit or power”. Many learned to use a mix of inauthentic or pay-for-play amplification mechanics, coupled with psychological manipulation techniques and exploitable platform asymmetries to their advantage. Propaganda is just one word to describe the tools and tactics from information warfare. In the “battle space of information”, as disinformation researcher Carl Miller thinks about it, information combatants fight over large patches of our shared public square. Attention is might in the information age, and the winners take all.

We see the results of that information warfare every day. A lot has been written about the corrosive impact of misinformation or disinformation in society, or the distortion of reality perception on social media. Yet we have merely scratched the surface. Renee DiResta sees the problem much bigger; the fragmentation of society into bespoke realities of our choosing.

Everybody gets a customized news feed or algorithmically curated content based on their engagement, biases, and unaccountable search & ranking algorithms. On top of that, we are exposed to the most successful information operations and deep-pocketed, grassroots, or populist propaganda, in fact, we mostly contribute to it. In the online marketplace of chose-your-own-reality, those who can deliver the desired “alternative facts” and motivated rationalizations to justify whatever we intuitively want to be true, or those in power want us to buy into, often get rewarded richly. Distortions of reality are bottom-up and top-down, with influencers often serving as critical gatekeepers for dissemination. Neither is a neutral party.

So day in and day out, we engage, act upon, and build our identity on the most salient narratives and compelling fictions that are increasingly detached from objective reality, shaped by forces, actors, and incentives we don’t understand, and that are not accountable to us or society.

Once we get captured by some of those engaging fictions, we engage and become part of tribal and bespoke online communities that formed around them. We also become defensive about contradictory facts, seeing them as an attack on our identity or our tribe. At this point, “the difference between information that is ‘good’ for our side, and information that is ‘true’ becomes nearly impossible to distinguish”, as computational sociologists Petter Törnberg writes in his book about extremist online communities. Yet we live in an interconnected world. For any major societal event, there will be dozens, if not hundreds, of compelling fictions to buy into; very few of them can be objectively true at the same time, and there will be plenty of communities vehemently opposed to most other particular understanding of the world.

Informational conflicts between different bespoke worldviews and objective reality are inevitable.

I believe it is these conflicts between shared reality and bespoke fictions that have increasingly put science and scientists (as well as investigative journalists, educators, and other defenders of an evidence-based worldview) under pressure from society, and into the crosshairs of those in power.

Their acts of anti-science aggression are what we see play out in real-time today, but how it works and who profits from these attacks is often less clear to outside observers.

Science challenges power, old and new

Science is a myth-buster. It challenges the convenient fictions we tell ourselves and debunks the narratives of those who seek to manipulate with falsehoods.

The scientific method has the inherent authority to create, assert, dispute, challenge, and correct information, thus it is the ultimate arbiter of solving informational conflicts or contradictions and defines shared reality. It may offer one of the greatest services to an enlightened society by allowing the formulation of a consensus reality based on shared facts.

But in a world of bespoke realities, science has become a threat not only to shady businesses, pseudoscience peddlers, and religious ideologues but also to some powerful financial interests, influential media outlets, political movements, identities, and communities.

Their agents of influence all gain power by undermining the authority, function, and perception of science. Instead of a shared public good that shares its fruits equally with democratic citizens, no matter who they are or what they believe, these agents, activists, and agendas aim to portray science and scientists as fundamentally corrupt and untrustworthy. They cast scientific knowledge as the opinion of a weird secretive niche interest group, tribe, or cabal. They treat inconvenient scientific research as ideologically subversive, something that needs to be beaten in the fight for societal supremacy, public perception, and political power.

I have previously written three articles explaining some of the communication tactics these anti-science activists and media manipulators use to sow doubt about scientific topics that interfere with their particular financial interest, identity, or political worldview:

This type of anti-science activism has become a necessity for old and new powers in the information age who want to entrench their particular worldview and consolidate their grip over public discourse, and with it, wider society.

These are the larger trends science and society face.

But now I want to more concretely comment on some of the few recent events that have been driven by a confluence of grassroots activists, media amplifiers, and elected representatives in the US Congress.

Because one scientist’s crisis is another shyster’s opportunity.

The inner workings of an anti-science ecosystem

When we think about the recent attacks on science and scientists, we observe partially overlapping, partially independent communities, actors, and actions both on the left and on the right, both from fringe figures as well as elected representatives, amplified by mainstream and alternative media outlets.

This is confusing because we have a very linear understanding of how coordinated attacks work; meaning we presume that one actor, group, or party is the organizing mastermind behind all activity.

Yet this is not reflective of a world fragmented by bespoke realities.

In today’s world, coordination arises through a complex, interactive process of shared narrative formation, enabled by information technology. Without going into the details here, we can think of co-created narratives and shared myths as the coordinating force that aligns various stakeholders to act collectively. The bigger the story, the more engaging and encompassing the myth, the wider the societal buy-in.

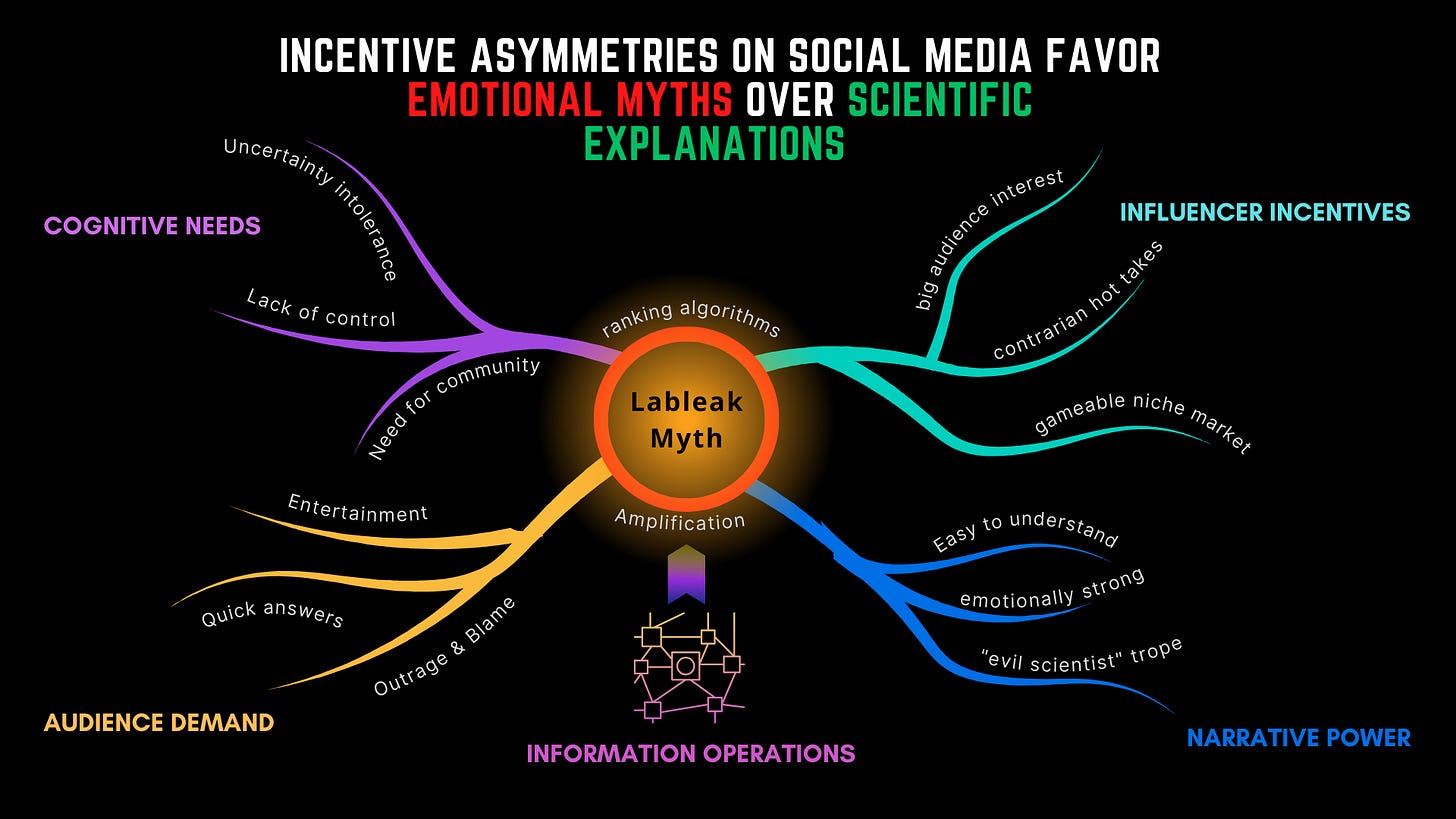

Especially emotionally activating myths have the advantage of getting a much larger societal buy-in than dry scientific explanations.

This is not entirely new, just to be clear. There is a long history of how propaganda and myth-making are used to shape collective action; in the early 20th century academics would even argue that it is the duty of the state to propagandize citizens for their benefit. (I highly recommend Renee DiResta’s book Invisible Rulers to get a more thorough treatment of this topic)

For our current purposes, it is useful to think of a “narrative” as the coordinating force, whereas human actions, desires, and incentives work at different, partially overlapping, societal layers to feed into the narrative and get rewarded by it. There is not one mastermind; but many agents of influence that each contribute a crucial piece to the total while gaining something important to them in return.

Understanding the motivations of discourse shapers

Well, since I have been mostly versed in the particularities of the discourse surrounding the origins of COVID-19, I will take the false “lab leak” narrative as a case example to highlight how the different layers of that particular anti-science ecosystem act together to attack science and scientists and gain rewards for doing so.

Let’s start with a very obvious one:

1) Conspiratorial communities and hate groups

“On the individual level, people are attracted to these conspiracy theories when they have a psychological need that is not met”, Prof. Karen Douglas explained to me. The research professor from Kent in the UK had studied conspiracy theories and their believers for decades when it was still considered a niche topic. She has found that believers are mainly driven by epistemic, existential, or social motivations; the need to make sense of our world and circumstances, the fear for their lives or livelihoods, or the feeling of social ostracism and disconnect. “If you are scared, disgruntled, feel left behind, resentment… it’s this whole cluster of negative feelings and attitudes and fears that gets people into a space where conspiracy theories seemingly offer a solution”, the cognitive psychologist Prof. Stephan Lewandowsky elaborated. Especially pandemics, economic recessions, and traumatic events, such as the loss of a loved one, create the conditions for conspiracy myths to thrive. That these conspiratorial explanations for a traumatic event are inherently adversarial to an out-group is no coincidence either. Believing and meeting other believers can offer a sense of community and form real social bonds and identities; they are united against a common and often nebulous enemy. The deep state, the scientific establishment, big pharma, the liberal media, the bank cartels, or the Jews would be common tropes for those enemies. None of that is exactly new, but rather much more ancient. Blaming somebody else is how we humans have always reacted when we feel powerless to control our own circumstances, and blaming a deadly virus on scientists is no different.

2) Inauthentic amplification

While there are many “lab leak” myths, one of the first ones that became popular was the idea that SARS-CoV-2 was a Chinese bioweapon. Already in January 2020, the fake dissident and Chinese billionaire Miles Guo, working closely with Steve Bannon, would create this narrative in their efforts to undermine the Chinese Communist Party and win over followers and true believers for their cause to exploit them. Their media operation including bot networks, sock puppet accounts, the portal Gnews, as well as an array of paid amplifiers from the Chinese-speaking diaspora surrounding the influencer Lu De got the ball rolling; garnering 143 million views in just a few months. They would also cultivate a fake whistleblower named Dr. Li Meng Yan who would become a rightwing media sensation later in 2020, with dozens of media appearances on Fox News, Tucker Carlson, OAN, Bannon’s war room podcast, etc. Ultimately, Miles Guo has fleeced his followers out of a billion dollars with fraudulent investment schemes, a dramatic return of investment for his digital operations.

3) Influencers and community leaders

The goals of influencers are mostly self-serving but fall roughly into the categories of popularity, persuasion, profit, or power. Sometimes all of them combined. Dr. Alina Chan has been one of the leading lab leak influencers who rose to prominence by bringing various conspiracy theories from the periphery of social media to the center of society. At a time when the idea of a man-made virus was discarded (accurately) as sinophobic narrative pushed by the Trump administration, she got picked up by the conservative activist and climate change denier Matt Ridley to present a more left-leaning and polite version of the same accusation. A regular contributor to the Wall Street Journal’s opinion pages, the Telegraph, and many other mainstream outlets, Ridley was a veteran manipulator of ideologically inconvenient scientific issues. He probably saw the potential of a young, presentable, media-hungry contrarian researcher with the credentials of elite academic institutions. They struck up a collaboration that would soon yield one of the most manipulative works of fiction of the pandemic origins; and catapulted Alina from the unremarkableness of her academic work into the global spotlight.

4) Sponsored activists and shady pressure groups

USRTK was originally conceived as a left-wing anti-GMO – genetically modified organism – pressure group to target inconvenient scientists and advocates with harassment. Bankrolled largely by the Organic Consumer Association – who funded USRTK to the tune of over 1 million dollars between 2014-2021 – the activists' modus operandi was to abuse the Freedom-of-information-act (FOIA). Once USRTK receives thousands of their target’s documents from FOIA requests, they spring into action. They search meticulously those private messages for any snippet, connection, or oddity they can cherry-pick, decontextualize, and put in the worst possible light to smear scientists in the public's eye. In politics, this approach would sometimes be known as mudslinging; throwing a lot of dirt at the wall in the hope something will stick. As a result of these character assassination attempts, many scientists will choose to then disengage from public life. Who wants to get their private address leaked, their families harassed, or life threatened by malicious lies? There is a chilling effect beyond the individuals targeted. Many scientists might feel it is not worth the risk to continue speaking up about their research or evidence-based decision-making, certainly not in public. Yet this is exactly USRTK’s method behind the madness. “They extract a high cost for free speech, they coerce the informed into silence”, the prestigious journal Nature would write about USRTK in 2015. The moment inconvenient scientific voices are bullied into silence, activists are free to shape public discourse and emotions on a scientific topic in their preferred direction. “This is how demagogues and anti-science zealots succeed”, the journal Nature concludes. Unsurprisingly, when the fear of “genetically modified viruses” was dangled in front of such a ruthless organization, they saw an opportunity to expand their mission, scope, and influence. From Frankenfoods to Frankenviruses, so to speak. In the summer of 2020, USRTK had started to abuse FOIA to gain communications between virologists and the NIH to cook up a narrative about gain-of-function research causing the pandemic.

5) Opinion shapers and tastemakers in mainstream media

The Daily Mail and the New York Post (DMGT and Murdoch-owned tabloids) have been at the forefront of pushing the false lab leak myth into the world. Salacious rumors, sensationalist headlines, innuendo, and speculations all drive clicks and engagements, and with them profits and influence over society. But the real power of opinion shapers comes with selling pseudoscientific rationalizations to audiences that want to believe in a red meat theory, without feeling like idiots for doing so. The opinion pages of the Wall Street Journal have been influential because they serve that function for the rich and powerful, and the op-ed desks from the Washington Post and more recently the New York Times are not far behind. These outlets cater to the powerful and offer their agendas legitimacy and pseudoscientific cover in exchange for access and influence.

6) Billionaire ideologues and elected politicians

The red-pilled mark and gullible megalomaniac of X repeatedly called for the prosecution of Fauci and has in general turned against an evidence-based worldview. He bought a whole social media platform to spread his ideology. The GOP-led House of Representatives has set up three committees to do revisionist propaganda for Trump and the MAGA movement. These actors fucked up the pandemic response and caused unspeakable suffering and death to many Americans. The House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus pandemic attempts to rewrite that inconvenient history of political failings by blaming the pandemic on scientists, all while creating a media spectacle in dragging innocent virologists, public health scientists, and even scientific journal editors into show trials to activate and mobilize voters for the election. But no matter if politicians or billionaires, these elites want to use power in service of their worldview.

The interesting and currently less understood part is how these various discourse shapers interact with each other to further their goals. Vested interests are found financing niche influencers or amplifying their content when it suits their agenda. Conspiracy theorists harass, threaten, bully, and attack opponents at the behest of politicians who are or pretend to be on “their” side. Activist organizations provide scoops and news stories for mainstream outlets that profit both organizations but at the cost of truth, trust, and transparency. Mainstream outlets platform conspiracy theorists to score political points with motivated audiences.

It is an unethical mess that is hard to understand for audiences not deeply familiar with the particular ecosystem and its shady dynamics. Everybody in that ecosystem has something to gain from collaborating; the only losers are science, scientists, and the public good.

Anti-science aggression

Now while I focused on some of the diverse players in the lab leak ecosystem just now, it is important to mention that the rightwing media outrage machine has cultivated these types of narrative-based activist ecosystems for a long time. Against social progress and racial justice, against climate action and the Green New Deal, against women’s rights and abortion, take your pick. These ecosystems always also include connivance and opportunists from ostensibly left-leaning actors, organizations, and crowds.

Shaping the discourse of millions, and with it the thoughts, opinions, identities, and communities around them, is extremely powerful. It can also reward those information combatants who do it best tremendously.

Even if you do not care about science, we all would do better to learn quickly how narratives get formed in our fragmented realities.

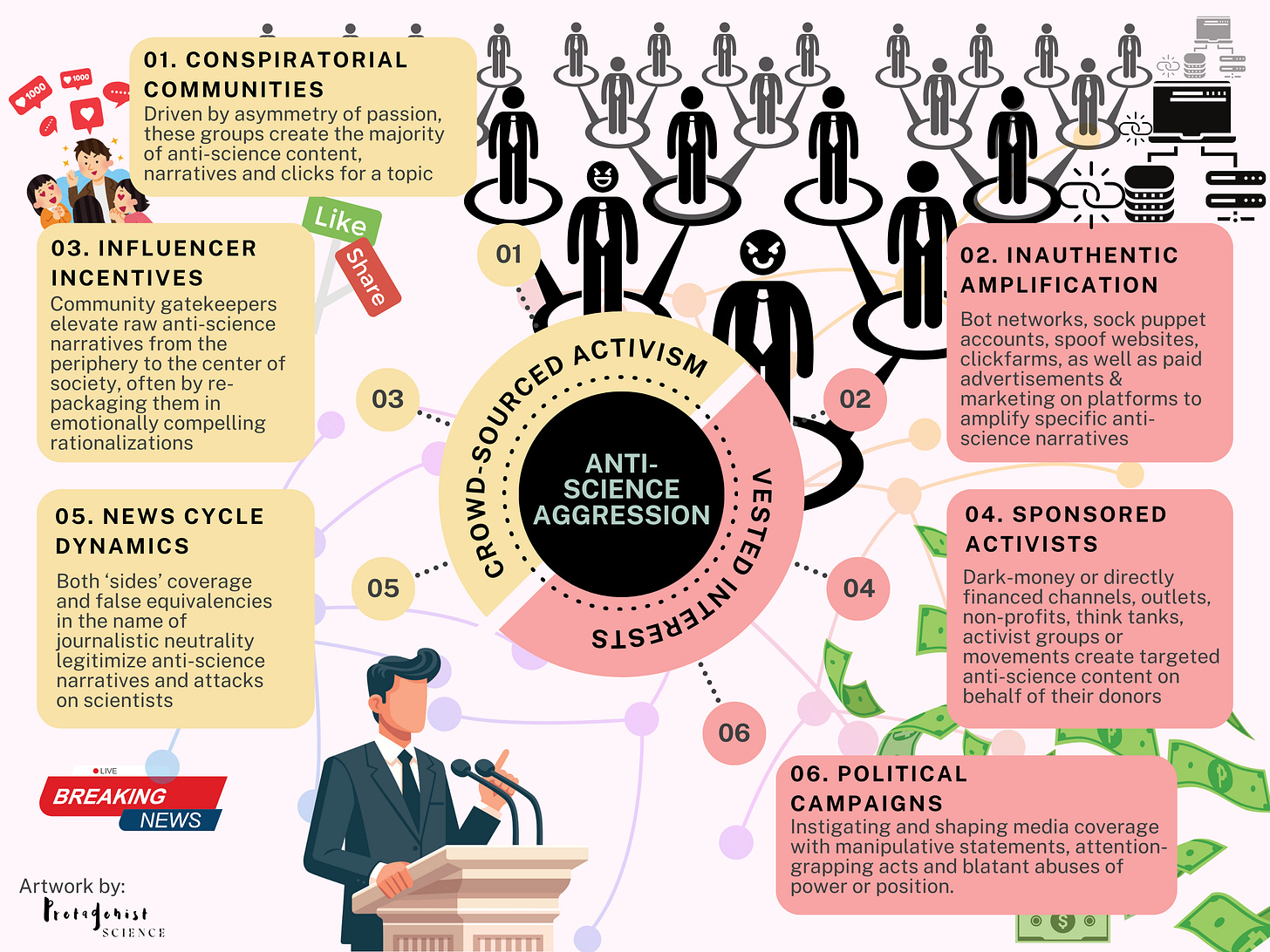

If you care about science, here is a handy infographic I made for you:

Unfortunately, it seems that anti-science aggression has become inevitable in a world of bespoke realities and a time of grand narratives.

What are the consequences?

Fear, fury, and forbearance are haunting US scientists

Bespoke realities have created new power centers in our midst; Renee DiResta talks about crowds, algorithms, and influencers at the core of the Fantasy-Industrial Complex. She has been its latest victim.

She was targeted for the sin of studying how these new power centers behave and interact with society. Two days ago, plagued by spurious lawsuits, conspiracy theorists, client propagandists, and the elected representatives abusing the power of the state, her research group at Stanford was terminated. (Read her story here)

Having a broad anti-science ecosystem aligned with a grand narrative is scary and dangerous for any scientist whose research tends to interfere with said narrative.

Scientists are a minority in every society they are embedded in. Science values evidence over tribal affiliation, which is why it has no friends among political camps or extremists that tend to spearhead attacks on them. Because scientists are just not part of any larger political tribe, and most of society is oblivious to what happens to them in today’s fragmented information ecosystem, nobody comes to their defense when anti-science aggressors come for them.

This has some very direct consequences:

Inconvenient scientists are picked off one-by-one

Anybody who speaks up might become the next target

Nobody is safe to pursue independent research that might interfere with popular beliefs or power

In the last few months, I have witnessed events that I thought were largely impossible in a democratic society, yet they happened. I have had conversations with scientists who do not feel safe, who self-censored, or who stopped communicating to the public entirely. I have seen essential research projects scrapped, defunded, and scientists fleeing into less controversial areas of research to protect their careers, their lab members, and their families.

When your private messages can get subpoenaed by political activists and leaked to their client propagandists to start a smear campaign, would you feel comfortable talking about a controversial topic even in private?

When New York Times columnists work closely with conspiracy theorists to build their hit pieces against you, are you comfortable speaking up for scientists even as a bystander?

When you get dragged in front of Congress in a witch hunt, where they lie about you to your face and afterward refer you to criminal prosecution, do you want to roll the dice that the justice department still has not been captured by the institutional rot impacting every other area of government?

When you have to change your home address and scrap the internet of private information because you and your family receive daily death threats from hate groups, do you have the capacity to continue your work?

I wish I talked in the hypothetical, but it is not a great time to be a scientist, doctor, or investigative journalist working on a controversial topic in the US; and these topics somehow include vaccines, climate, disinformation, or virology.

At what point do we stop talking about individual scientists or topics?

At what point do we realize that all of science, and with it an evidence-based worldview, is under pressure?

Conclusion

The recent months have been a time of loss and peril for science and scientists.

But the consequences for society might even be more dire.

The scientific method has the inherent authority to create, assert, dispute, challenge, and correct information, thus it is the ultimate arbiter of solving informational conflicts or contradictions and defines shared reality. It may offer one of the greatest services to an enlightened society by allowing the formulation of a consensus reality based on shared facts.

What happens when that service is no longer available to society? Reality has this unwelcome feature that it does not care what we believe. A deadly virus does not care whether you reject germ theory. A climate change-intensified drought does not care whether our crops die or we starve.

Only when information and reality perceptions are grounded in scientific reality, will we be able to ensure that productive cooperation towards shared goals remains possible for any democratic society.

In contrast, undermining science and an evidence-based worldview creates an epistemic crisis. It makes all informational disputes perpetual, our fights over reality unresolvable, and collaborative action on important topics like climate change, and pandemic prevention impossible.

It might make peaceful co-existence in a democratic society impossible.

“Without facts, you can’t have truth. Without truth, you can’t have trust. Without all three, we have no shared reality, and democracy as we know it— and all meaningful human endeavors — are dead.”

- Nobel Laureate Maria Ressa

Science is a critical guardrail to democracy that is being dismantled in front of our eyes today.

I have been writing about the encroaching of a new dark age of myth, manipulation, and magical thinking that seems to be upon us. Yet my warning is not new:

I have a foreboding of an America in my children’s or grandchildren’s time — when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority; when, clutching our crystals and nervously consulting our horoscopes, our critical faculties in decline, unable to distinguish between what feels good and what’s true, we slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness… — Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World

If scientists are canaries in the coal mine of democracy, the carbon monoxide has already filled the chamber.

Beware your next steps.

Update 17.05.2024:

An earlier version of this article referred to “A non-profit that was debarred […]”; more accurately, the non-profit is currently “suspended” from federal funding and was proposed for “debarment”.

19.06.2024:

The article was updated to correct that Daily Mail and New York Post had different owners, only the latter being Rupert Murdoch. I thank John Seal for pointing out the mistake.

It's a minor point, but while the Daily Mail IS a rabidly right-wing tabloid, it is NOT owned by Rupert Murdoch. It's owned by Viscount Rothermere. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daily_Mail_and_General_Trust